A study published yesterday in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) indicates that the fossils of Late Pleistocene big cats once believed to have been tigers were actually cave lions. The fossils were, for the first time, analyzed genetically as opposed to morphologically, which led to these intriguing conclusions.

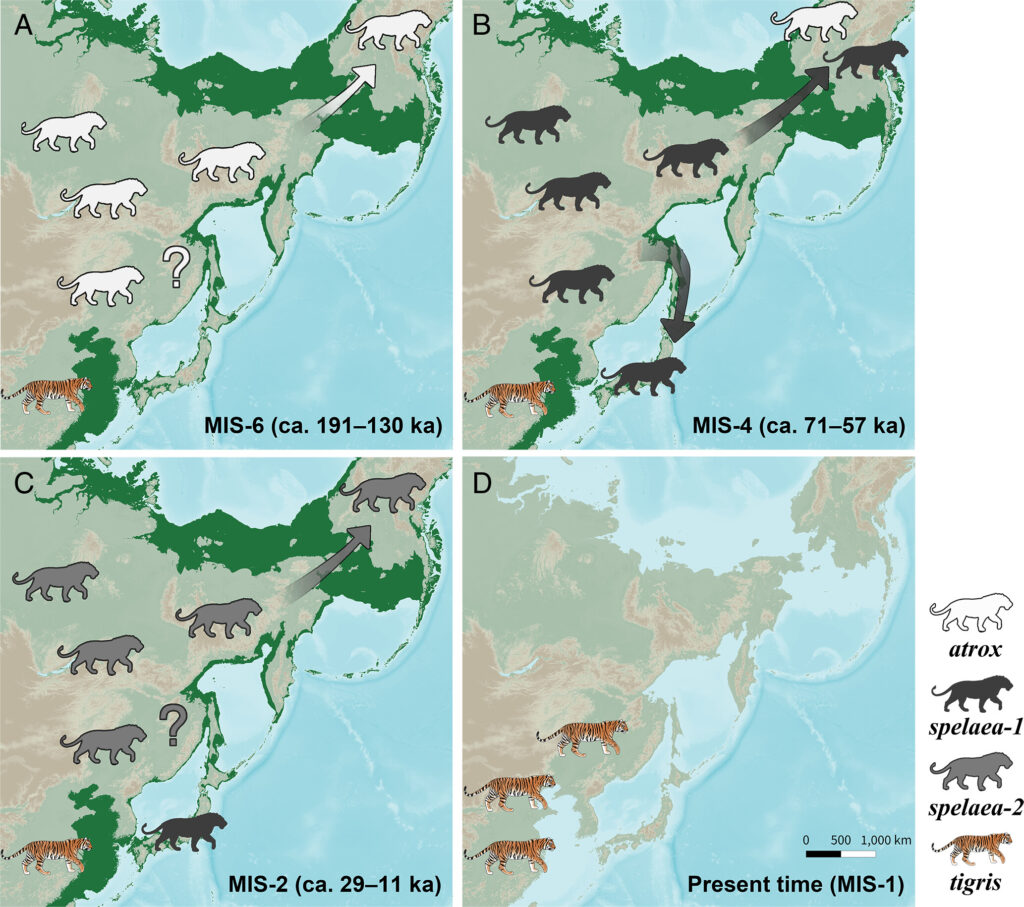

It’s well known that both tigers and cave lions existed in northeast Asia (northern China, southeastern Russia, and Korea) during the Pleistocene. It’s possible that despite generally preferring different habitats, they may have overlapped at the edges of their ranges and potentially encountered each other. I have written about the presence of tigers and cave lions during the Late Pleistocene in Primorye in the Russian Far East, with the former occupying the area during warmer, more forested intervals and the latter during colder, more steppic ones. It’s worth noting, however, that the tigers found in northeastern China and southeastern Russia appear morphologically and genetically diverged from modern-day tigers, including Amur tigers.

Japan adds an interesting dimension to this story, as it’s an archipelago (island chain) with a long history of isolation but also periodic connections to the mainland. It’s known that during the Pleistocene, cold-adapted steppe fauna like woolly mammoths and steppe bison colonized the Japanese archipelago from the north using past land bridges connecting it to Sakhalin and ultimately mainland Siberia. However, it was believed that the big cats found in Japan were tigers rather than lions on the basis of morphological analysis of their remains as well as the persistence of temperate forests in large parts of Japan. Until now.

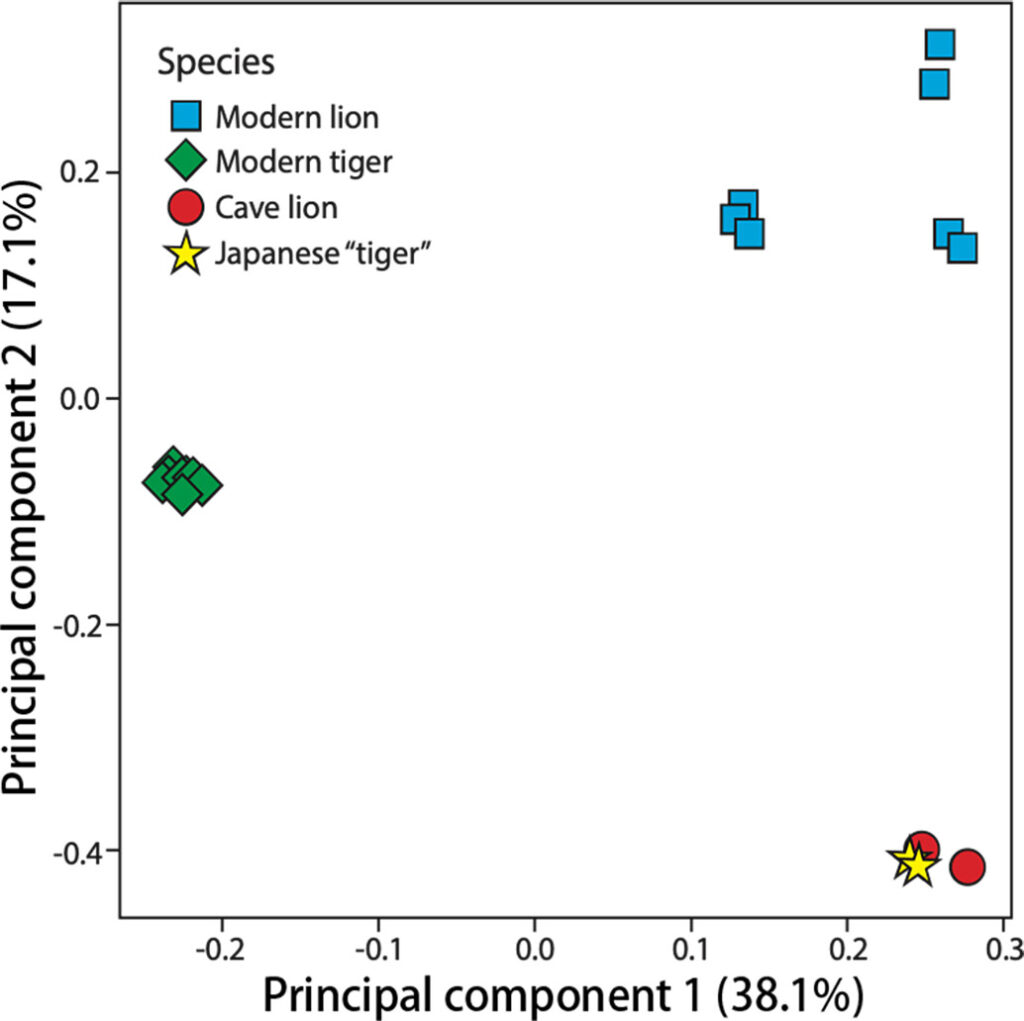

“Tiger” remains from three separate parts of Honshu Island—north, center, and south—all turned out to actually be cave lions as indicated by their mitogenomes. The cave lions specifically belonged to a clade known as “Spelaea-1” which was once prevalent in eastern Beringia (northwest Canada and Alaska) prior to going extinct and being replaced by a different clade of cave lions (Spelaea-2).

The presence of cave lions in northern, even central Japan during the coldest periods of the Pleistocene wouldn’t be too surprising. However, it is incredible that even those in the far south of Japan, in Yamaguchi Prefecture, also turned out to be cave lions considering that southern Japan was long considered to be highly suitable habitat for tigers during that period.

While a land bridge seemingly existed between northern Japan and Russia during the Late Pleistocene, it’s not known if southern Japan was also connected to the mainland via Korea during that period. I would speculate that a potential lack of a southern connection during the Late Pleistocene prevented tigers from colonizing southern Japan despite the ostensibly suitable habitat there, whereas lions could colonize it after reaching Japan via the northern land bridge. It could also be that Japan was once colonized from the south by tigers, perhaps during the Middle Pleistocene when land bridges connecting to Korean are known to have existed, but went extinct later.

Either way, this is an extremely edifying study and I’m hoping to see more like it. Late Pleistocene East Asia doesn’t get enough attention.

References

Sun, X., Peng, L., Tsutaya, T., Jiangzuo, Q., Hasegawa, Y., Hou, Y., Han, Y., Zhuang, Y., Ramos Madrigal, J., Taurozzi, A. J., Mackie, M., Trochė, G., Olsen, J. V., Cappellini, E., O’Brien, S. J., Gilbert, M. T. P., Yamaguchi, N., & Luo, S.-J. (2026). The Japanese Archipelago sheltered cave lions, not tigers, during the Late Pleistocene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 123(6). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2523901123

Yoahikawa, S., Kawamura, Y., & Taruno, H. (2007). Land Bridge fomation and proboscidean immigration into the Japanese Islands during the Quaternary. Journal of geosciences Osaka City University, 50, 1-6.