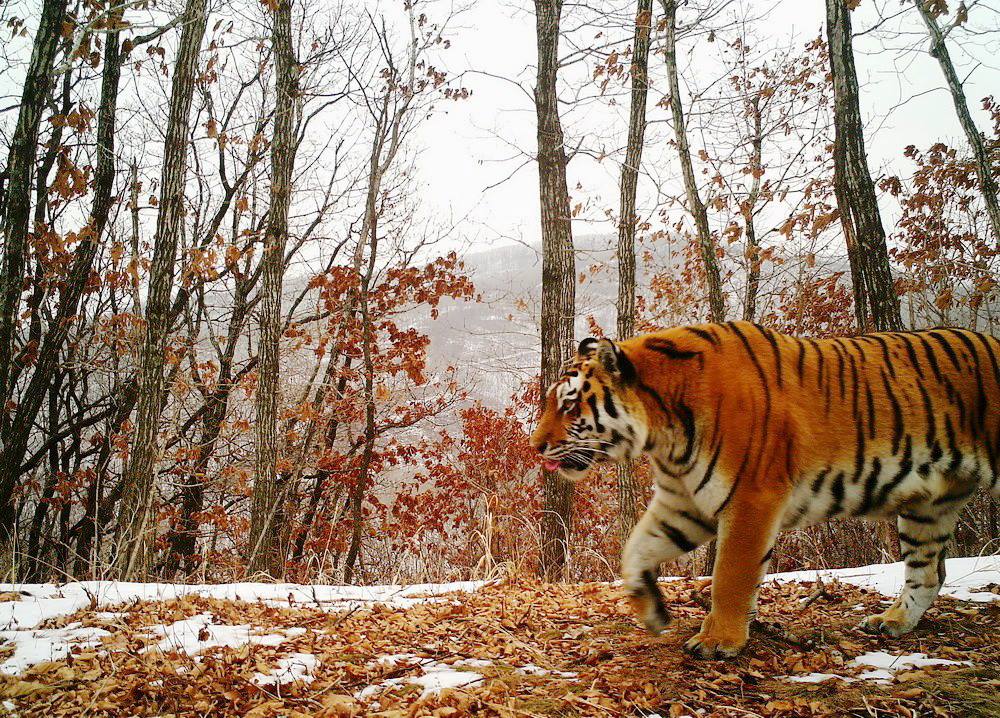

See the forests in the pictures above? They are located in the Sikhote-Alin mountains in the Russian Far East. While undoubtedly scenic, a person not familiar with biodiversity in this part of the world may not understand what is so special about them. After all, they more or less just resemble forests in much of temperate Europe and North America. Yet, they hide many secrets.

These forests are best known for being the main refuge of the endangered Amur (or Siberian) tiger. As a kid, I was always fascinated by wildlife and tigers in particular, and I was intrigued to learn that tigers lived in southeastern Russia and shared their habitat with Asiatic black bears, brown bears, wapiti, moose, and the extremely endangered Amur leopards. This region has captivated me ever since.

Amur tigers are often described as a boreal or taiga species, but its habitat is actually classified as a temperate rainforest and is climatically and ecologically much more similar to areas of nearby northern China and parts of the Korean peninsula than with core areas of Siberia. It is strongly under the influence of the East Asian monsoon with most rain falling during summer months, and the forests are dominated by Korean pine, Jezo spruce, Khingan fir, Mongolian oak, and other species typical of the East Asian region. In fact, it is historically part of Manchuria.

Biodiversity is greater here than it is in the taiga biome to the north, likely owing to the milder climate. However, winters can still get quite cold even at coastal locations like the Russian port city of Vladivostok. This is due to the Siberian high, which produces extremely cold and dry weather that causes winters in northern Asia to be much more frigid than at the same latitudes in North America or Europe.

Southeastern Russia and the adjacent parts of China and Korea were home to a very different type of environment during the Late Pleistocene. The area was not glaciated except at higher altitudes because the Siberian high would have created exceptionally dry conditions during winter with very little snow. Still, it was obviously colder, and most of the same ice age animals found across northern Eurasia were found here too like mammoths, steppe bison, cave lions, cave hyenas, and woolly rhinos alongside animals still extant in the region like tigers, brown bears, elk, and moose1 2, although it is likely that not all of these animals were present simultaneously.

When mammoths, steppe bison, and woolly rhinos roamed the coastal region of southeastern Siberia, it was wetter than more northerly (Arctic) or westerly (northeastern Chinese) areas. This is evidenced by isotopic analysis on the remains of the animals which show relatively low Nitrogen-15 values, while palynological studies show that the area was not a dry, treeless steppe but rather a mixture of boreal forest composed of larch and birch trees along with shrubs and steppe1. It may have been better described as a kind of forest-steppe or boreal woodland rather than mammoth steppe, and reveals a degree of ecological plasticity among the herbivores living there.

As someone involved the paleo-community, I have seen fellow animal enthusiasts speculate about whether or not Amur tigers coexisted with iconic ice age megafauna like woolly mammoths or cave lions, with occasional paleoart even depicting such encounters-here and here for example. However, Amur tigers themselves are relatively recent (early Holocene) arrivals to the region, likely from Central Asia3.

Yet, tigers in general have been there for much longer than that. Fossils of tigers have been found in the Geographical Society Cave in Primorye, although these appear to be morphologically distinct from modern Amur tigers2. A study that genetically analyzed a Pleistocene tiger mandible from a cave in northeastern China found that the animal belonged to a lineage that was deeply diverged from modern tigers, splitting from modern tigers 268 thousand years ago, while modern tigers share a common ancestor with each other 125 thousand years ago4. So tigers were present here during the Pleistocene-the lineage or lineages in question would have simply been quite distinct from modern ones.

Radiocarbon dates from the Geographical Society Cave show that fossils of tiger and mammoth steppe animals (cave lion, mammoth) were separated by time, with around 2000 years separating the latest tiger from the earliest woolly mammoth in MIS 35. Tigers tended to be present during warmer intervals while mammoths were present during colder ones. However, due to Signor-Lipps effect, these probably do not represent the last tigers or first woolly mammoths to occupy that region within that time slice. That raises the intriguing possibility that there may indeed have been encounters between tigers and extinct ice age fauna in that part of the world.

The steppe-associated herbivores had no problem living near areas of substantial forest in coastal southeast Russia, so it should not come as too much of a surprise if there was some degree of transitional habitat where two different faunal sets-temperate forest and glacial steppe-met one another. The southernmost woolly mammoths made it into north-central China (Shandong province) after all6, so I would be shocked if they did not cross paths with tigers somewhere between there and the Sikhote-Alin. We have no way of knowing what these interactions would have been like or how frequent, but it is an exciting thought nonetheless.

References

1. Ma, J., Wang, Y., Gennady Baryshnikov, Drucker, D. G., McGrath, K., Zhang, H., Hervé Bocherens, & Hu, Y. (2021). The Mammuthus-Coelodonta Faunal Complex at its southeastern limit: A biogeochemical paleoecology investigation in Northeast Asia. Quaternary International, 591, 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2020.12.024

2. Baryshnikov, G. F. (2016). Late Pleistocene Felidae remains (Mammalia, Carnivora) from Geographical Society Cave in the Russian Far East. Proceedings of the Zoological Institute RAS, 320(1), 84–120. https://doi.org/10.31610/trudyzin/2016.320.1.84

3. Driscoll, C. A., Yamaguchi, N., Bar-Gal, G. K., Roca, A. L., Luo, S., Macdonald, D. W., & O’Brien, S. J. (2009). Mitochondrial Phylogeography Illuminates the Origin of the Extinct Caspian Tiger and Its Relationship to the Amur Tiger. PLoS ONE, 4(1), e4125. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0004125

4. Hu, J., Westbury, M. V., Yuan, J., Wang, C., Xiao, B., Chen, S., Song, S., Wang, L., Lin, H., Lai, X., & Sheng, G. (2022). An extinct and deeply divergent tiger lineage from northeastern China recognized through palaeogenomics. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 289(1979). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2022.0617

5. Kuzmin Y.V., Baryshnikov G.F., Timothy J., Orlova L.A. and Plicht J. van der. 2001. Radiocarbon chronology of the Pleistocene fauna from Geographic Society Cave, Primorye (Russian Far East). Current Research in the Pleistocene, 18: 106–108.

6. Takahashi, K., Wei, G., Uno, H., Yoneda, M., Jin, C., Sun, C., Zhang, S., & Zhong, B. (2007). AMS 14C chronology of the world’s southernmost woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius Blum.). Quaternary Science Reviews, 26(7-8), 954–957. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2006.12.001