There are few places in this world more captivating than the Amazon. While the Amazon biome includes the famous Amazon rainforest as well as adjacent ecoregions, the term “Amazon” usually refers principally to the rainforest itself. Located within the Amazon basin, it is home to the mighty Amazon River—the largest river by water discharge and either the longest or second longest in the world—along with its many tributaries.

The Amazon rainforest is the largest of all rainforests and contains the greatest concentration of plant and animal species anywhere in the world. It’s also quite ancient; it’s believed that it’s been around for tens of millions of years. Given its great size, the Amazon is also home to a number of uncontacted indigenous tribes. Unfortunately, huge parts of it are currently threatened by deforestation.

I visited the rainforest a little over a decade ago when I went to Brazil. While my memory is somewhat fuzzy, I do still recall the powerful feelings this trip inspired in me. Although I only got to see a small section of the central Amazon, I could easily sense the vastness of this wilderness. The thought that the jungle stretches from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the foothills of the Andes in the west still fills me with awe. I also remember being almost unnerved by the monstrous size of the Amazonian rivers. They’re so wide that up close, it can be hard to tell that they’re not just huge lakes.

As this blog concerns the Pleistocene, we’re going to look into what the Amazon was like during ice ages. The ways in which it was different, and perhaps more significantly, the ways in which it wasn’t. There’s a lot of controversy regarding the exact character of the rainforest, with the greatest disagreement being over its geographical extent. Some advance a common view that it was fragmented and shrunken, with expansive tracts of savanna penetrating deep into areas where rainforest currently exists. Others, instead, argue that the Amazon basin remained heavily forested, albeit with a floral (plant) composition rather different from today.

One of the main goals of this blog is to present scientific information as accurately as possible, so I will do my best to communicate what the evidence actually shows when it comes to this topic. That is, although important changes certainly took place in the Amazon rainforest, it has most likely been robust and highly resilient throughout the ice ages of the last few million years.

Biogeographical Context

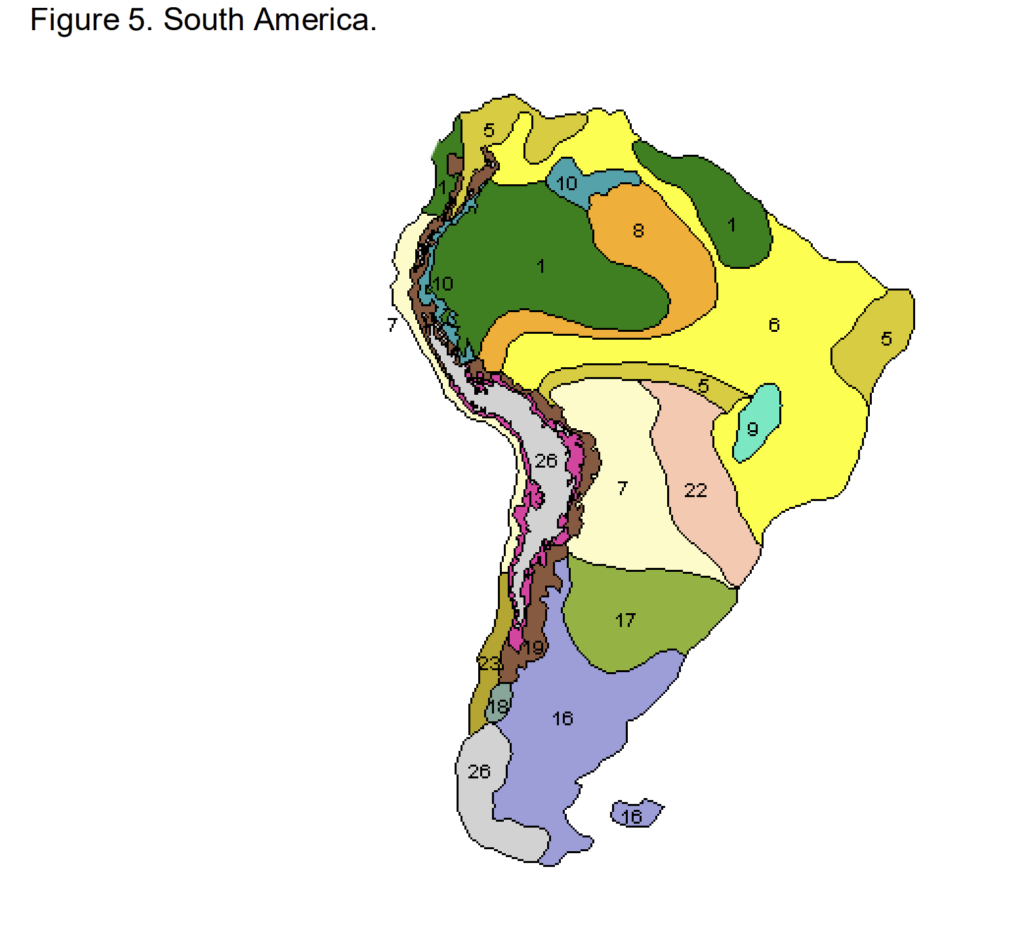

The Amazon rainforest is enormous and as such is not one monolithic block of jungle but contains a variety of different moist forest ecosystems. Some of these forests are flooded during a large part of the year. The westernmost fringes of the rainforest are of a montane variety and sit on the foothills of the Andes. They are cooler than the lowlands. At its northern and southern edges, the rainforest gives way to a variety of dry/seasonal forests such as the Chiquitano and Mato Grasso forests as well as grassland and savannas like the Llanos and Cerrado.

The enormous amount of rain that falls over the Amazon basin feeds gargantuan rivers that feed into the largest river of them all, the Amazon River. The discharge, or the amount of water that flows into the ocean, from the Amazon is greater than the next 7 largest rivers combined. The largest city in the Amazon rainforest is Manaus in central Brazil, located at the confluence of the River Amazon and Rio Negro.

Contrary to expectation, the western Amazon, located furthest away from the Atlantic Ocean, is wetter than the eastern Amazon. This is because rainfall is recycled over the rainforest: the trees absorb water and transpire it through their leaves, which then falls as rain further west. This recycling is essential to the rainforest’s resilience—it provides critical moisture during the driest months, such that pronounced dry seasons are mostly absent in Amazonian forests.

The Amazon contains an exceptionally high degree of biodiversity, not just as a whole but per any given unit of land area as well. It’s widely accepted that more species live here than anywhere else on the planet. Some have sought explanations for the sheer richness of animal and plant species, and this is where the debate over the character of ice age Amazonia comes in.

The Pleistocene Refugia Hypothesis

An interesting hypothesis has been put forth, promoted by Jürgen Haffer in 1969, which claims that “glacial aridity” caused the Amazon rainforest to contract greatly into a number of moist patches surrounded by drier savanna, which caused organisms located in different patches to diverge from each other. Once the patches expanded again to form a single unified forest during moist interglacial periods, the various lineages were brought together. Thus, the great diversity of the Amazon can be explained via allopatric speciation during the creation of multiple rainforest “refugia” during ice ages.

The basis for the concept rests on the notion of aridity being intense and pervasive globally during glacial periods. As there was limited data for the Neotropics, inferences were taken from tropical Africa, where there actually is evidence for major forest retreat during glacials. Purported geomorphological evidence for intense glacial aridity in South America and the Amazon in particular was posited by Chalmers Clapperton in 1993. He pointed to the alleged presence of extensive palaeodunes in regions outside of the Amazon basin such as in the Llanos, Pantanal, and Northeastern Brazil as well as the existence of sand deposits within the northwest Amazon during the last glacial.

From my general impression, the notion of a great mass of savanna dissecting the rainforest in some form still appears to be rather influential. The Wikipedia article on the Last Glacial Maximum claims that “The Amazon rainforest was split into two large blocks by extensive savanna”, something also depicted by maps of LGM biomes. The Wikipedia article on Guianan moist forests, part of the Amazon rainforest, states that savanna patches in the forests are remnants of savannas that may have covered all of Suriname during the Pleistocene. Search results from Google AI also claim that the rainforests of Amazonia were shrunken and fragmented.

Admittedly, there is quite an allure to the idea that broad swathes of grassy plains once penetrated deep into what is now a dense, massive jungle, perhaps supporting great herds of animals. Yet, however compelling that idea may be, the currently available evidence points to it being wrong. Quite wrong, in fact. How do we know this?

The Myth of Rainforest Retreat

Scientists such as Mark B. Bush, Paul A. Colinvaux, Paulo Eduardo de Oliveira, and Francis E. Mayle have done phenomenal work on Neotropical paleoecology. They have been staunch advocates for Amazon rainforest stability, delivering powerful and sometimes scathing refutations of the notion of Pleistocene savanna-ization. The majority of the information presented in this article is derived from their research.

For a while, there was extremely sparse paleoenvironmental data from the Amazon basin, a problem shared with other parts of the tropics. Pollen data extending back to the Last Glacial Maximum around 21 thousand years ago or further was practically absent from there. However, although the availability of data still lags behind the rest of the world, we’ve made great progress over the last few decades.

Most Amazonian paleoecological records, derived from a variety of proxies, extend back only tens of thousands of years rather than hundreds of thousands of years or more. Even so, those tens of thousands of years of the Late Pleistocene and Holocene span such an exceptionally wide range of climatic conditions that we can confidently draw inferences about the Quaternary as a whole anyway. So what do the records show?

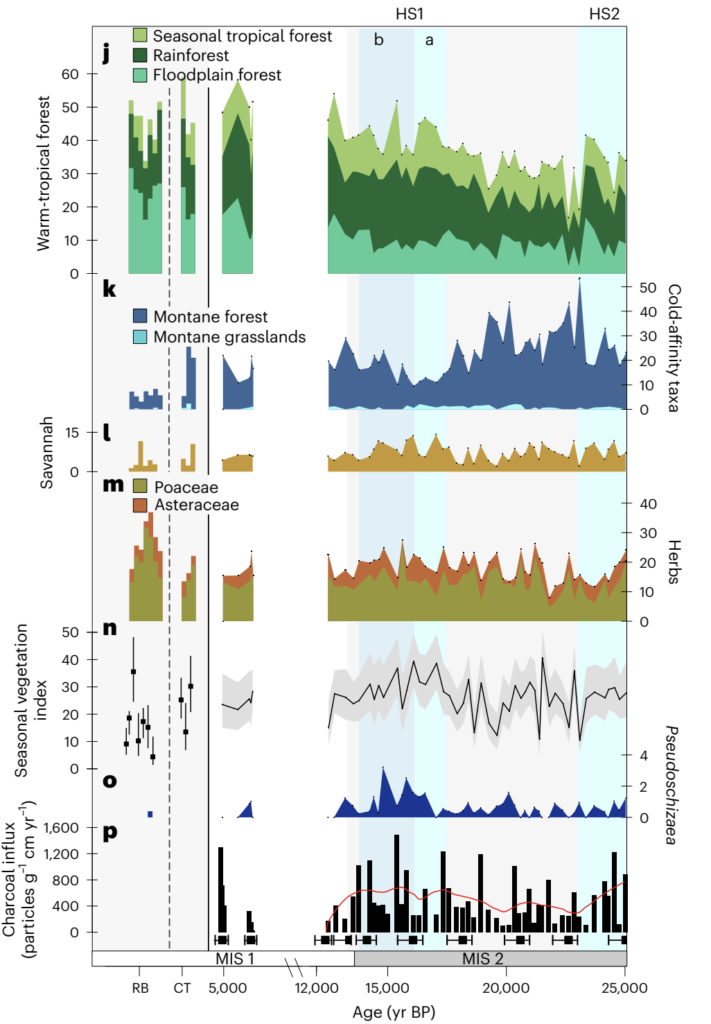

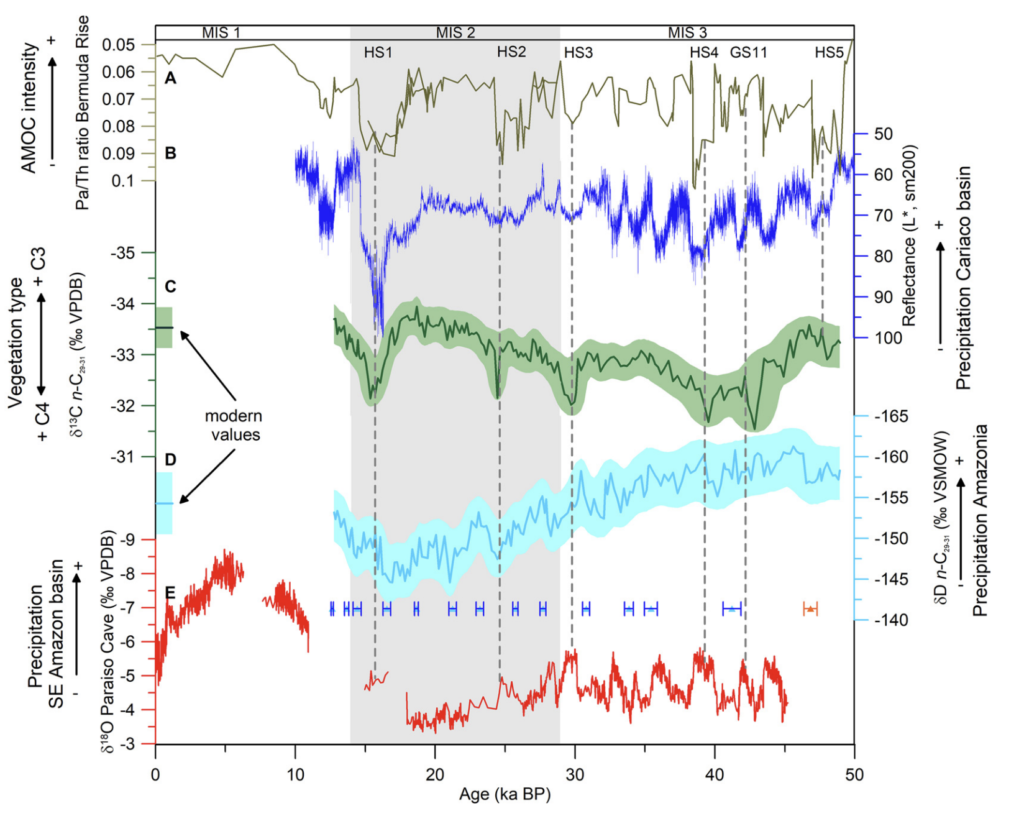

Pollen analysis of sediments taken from a number of Amazonian lakes indicates that forest cover remained high throughout the entirety of the last few tens of thousands of years, including the Last Glacial Maximum. In addition, marine cores off the coast of eastern South America provide basin-wide evidence of vegetation change, as sediments are carried directly from the Amazon River—with its many tributaries—to the Atlantic. Pollen data from these cores indicates continuous forest cover throughout the sequence, with no noteworthy surge in savanna elements such as grasses.

Isotopic analysis of these marine cores indicated the dominance of C3 plants rather than C4 plants, i.e. trees over savanna grasses. Additionally, fires are a common feature of savanna ecosystems, yet low charcoal inputs in LGM Amazonian sediments indicates minimal fire. To the extent that savanna replaced forest in the basin, this occurred only at the ecotones—the edges of the present rainforest in its northernmost, southernmost, and easternmost sectors. It’s also worth pointing out that the continental shelf was slightly extended, possibly providing extra area for rainforest and offsetting losses at the ecotones.

Further, critical analysis shows that the three supposed “glacial” dune fields in tropical South America do not support the idea of extreme aridity. The dune systems of northeastern Brazil were active during the Holocene as well as the Pleistocene, those associated with the Orinoco have uncertain ages, and the alleged Pantanal dunes are not even proven to exist. The white sands of northwest Brazil were actually formed as podzols under a humid climate. Phylogenetic splits between Amazonian species do not coincide with Pleistocene glaciations, and usually predate them. Ultimately, the concept of a very dry Amazonia where dense jungles greatly contracted and were replaced by savanna holds no water (pun intended).

Now, there is still a major difference between the rainforest of the glacial compared to that of the Holocene, and that lies in the temperature-affinities of the plant species that inhabited it. Mixtures of various cool-moist climate plants such as Podocarpus, Ilex (holly), Hedyosmum, Myrsine, Ericaceae (heath), and Drimys—which in tropical South America are now restricted mainly to higher elevations—are ubiquitous in glacial-age pollen sediments from the lowland Amazon. They existed alongside warmth-loving species typical of the lowland forest today, creating an ecosystem that partly bears a resembles montane Amazon regions like the Selva alta. Overall, however, the glacial plant assemblage lacks a proper modern analog. This is a recurring theme in Pleistocene ecosystems.

Paleoclimate simulations consistently underestimate the amount of cooling in the Amazonian lowlands, suggesting LGM temperatures somewhere between 1 and 2 degrees Celsius (°C) lower than today. However, the strong presence of the cool-climate taxa, later expelled from the lowlands following interglacial warming, mentioned above suggests a much larger cooling of around 5 °C. This is in line with estimates from studies on noble gases.

A picture emerges of a mostly-intact Amazon rainforest that was noticeably cooler than today with a different composition of plant species, but still warm enough to be filled with crocodilians, amphibians, and reptiles. This is fascinating to imagine. It was apparently not dry enough over the Amazon to induce widespread forest loss. However, this does not mean that it wasn’t any drier than today. Indeed, there is convincing evidence along multiple lines for drier than present conditions at certain periods. So how much drier was it really, and was this a problem for the forest?

Why the Jungle Survived

There actually is reason to believe that, at least during the peak of the last glacial period—the LGM—that conditions were overall drier over the Amazon basin. Paleoclimate simulations suggest that the decrease in evaporation over land was not enough to offset the decrease in precipitation. Although there was geographical variation, this meant generally drier conditions in Amazonia during the LGM. Lower-than-present lake levels, reduced river discharge, as well as isotopic data from leaf wax and speleothems provide evidence of this.

A reason why it would have been drier has to do with basic thermodynamics. Colder air can’t hold as much water as warm air, which means that in regions where the air tends to become saturated with water vapor, there is less moisture available for precipitation. Thus, the areas near the equator (roughly between 10° N and 10° S latitudes) were drier during the Last Glacial Maximum as this is the part of the world where moisture converges. And since the Amazon rainforest lies within these latitudes, it isn’t surprising that it followed this trend.

Isotopic studies from speleothems from the Paraíso cave in the east-central Amazon revealed substantially reduced precipitation compared to present during the LGM, with total rainfall being as much as 42% lower. Accounting for lower temperatures decreasing evaporation meant that moisture balance was around 20% less, but this is still a large reduction. Yet, other isotopic information from the speleothems reveals abundant forest cover during that period, despite the reduction in moisture taking place in a region that is already dry by Amazonian standards.

This combines with previously mentioned direct pollen data taken from offshore sites and lakes which indicates abundant tree pollen throughout the glacial period. So how was forest cover maintained in the basin under drier LGM conditions, especially considering that the lower CO2 of the period should have added water stress? There are a couple of intriguing potential aspects to consider.

variability” (Häggi et al., 2017) showing decreased moisture availability during the LGM than preceding and succeeding periods but high C3 vegetation

One is that most of the Amazon rainforest technically receives more rainfall and humidity than it actually needs, which means it can afford to take a cut. Further, paleoclimate simulations suggest that most of the decrease took place during the summer (wet season) whereas precipitation remained stable or even increased in winter (dry season). This is a crucial detail because there is a large surplus of water during the wet season, more than the plants can actually absorb.

Hence, a major decrease in wet season rainfall isn’t too decisive. The dry season, by contrast, is make or break for forests and rainforests especially. Longer and more intense dry seasons, as opposed to just less precipitation overall, are what separate grasslands and dry forests from rainforests. Indeed, it’s been hypothesized that in another part of the world where rainforests currently dominate—Sundaland—greater rainfall seasonality is what caused the expansion of grasslands during glacials.

The drop in wet season rainfall combined with stability or increase in dry season rainfall meant that although the total balance of water in the Amazon ecosystem was lower (hence the lower lake/river levels), this was not felt that sharply by the plants. I’d personally speculate that the lack of major fire activity during the LGM can be explained not just by lower temperatures, but also a lack of pronounced dry seasons (since those are when fires are most likely to occur). Ultimately, there was no drastic biome shift.

Additionally, it should be noted that environmental change in tropical South America isn’t a simple tug-of-war between rainforests and savannas, which complicates matters somewhat. You also have drier and/or seasonal forests, such as the Chiquitano dry forests and the Mato Grasso forests which fringe the Amazon rainforest. These seasonal forests occupy an intermediate position along the moisture gradient—they’re typically wetter than savannas but drier than true rainforest. Actually, there is substantial climatic overlap between dry seasonal forest and Cerrado savannas.

These drier seasonal forests, rather than savanna, could potentially have replaced rainforest in some sections of the Amazon basin when conditions become too dry to sustain the latter. Determining whether this happened can be difficult; it is challenging to differentiate rainforests from seasonal forests in the pollen record as families are commonly shared.

Interestingly, the “Pleistocene Arc Hypothesis” promoted by Darien Prado and Peter Gibbs in 1993 proposes that the range of dry forests expanded so much during glacials that now disjunct dry forest regions like the Chaco and Caatinga became connected. Unfortunately, much like the alleged savanna expansion in the Amazon, the evidence for these past connections is lacking.

Conclusion

All in all, there is currently no concrete evidence for a greatly contracted or fractured Amazonian rainforest during glacial times, even during the driest periods. The bulk of research indicates that conditions were rather cool compared to the present but still wet enough to support rainforest over most of the basin. Robust proof for the resilience of the forest through glacial times includes analyses of pollen, isotopes, and charcoal concentration in lacustrine and marine sediments. Though there is a possibility of some incursion of more dry tropical forests into the Amazon basin, savanna encroachment mainly occurred at the edges.

It should quickly be noted as this article comes to a close that the same pattern of cooler but moist/forested conditions during glacial times characterized the Atlantic Forest further south, underscoring the broader resilience and persistence of South America’s forests through history. It’s also worth pointing out that rainforest in tropical South America did not quite reach its modern extent until the late Holocene. Rainforest appears to have fully established itself in ecotonal (border) areas fairly recently—these areas were savanna-like during the early and mid Holocene. Hence, attempting to draw a sharp boundary between glacials and interglacials as it relates to biome extent is not advisable for South America.

So what’s the most parsimonious evidence for the extraordinary diversity found in the Amazon? The best answer might be that the combination of the rainforest’s stability, its deep age (perhaps 55 million years old), and its great size, as opposed to Pleistocene environmental fluctuations, are what allowed unparalleled species richness to build up over time. It might not be a coincidence that Neotropical rainforests were both more robust throughout time and are also more diverse than those in Africa and Asia.

Despite the research over the past few decades strongly refuting the notion of a fragmented Amazonian rainforest, the concept retains currency and is reflected in online discourse and literature. Why is this? I’d argue that it’s because the idea is alluring to many people. But I do believe in appreciating natural history for what it actually is, rather than what seems cool. And unless convincing evidence comes forward to support the notion of Pleistocene rainforest refugia, the idea should be abandoned or at the very least, viewed with a good amount of skepticism.

References

Akabane, T. K., Chiessi, C. M., Hirota, M., I. Bouimetarhan, Prange, M., S. Mulitza, Jr, B., C. Häggi, Staal, A., Lohmann, G., Boers, N., Daniau, A. L., Oliveira, R. S., Campos, M. C., Shi, X., & De, E. (2024). Weaker Atlantic overturning circulation increases the vulnerability of northern Amazon forests. Nature Geoscience. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01578-z

Alves, W., Lima-Ribeiro, M. S., Levi Carina Terribile, & Collevatti, R. G. (2016). Coalescent Simulation and Paleodistribution Modeling for Tabebuia rosealba Do Not Support South American Dry Forest Refugia Hypothesis. PLOS ONE, 11(7), e0159314–e0159314. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159314

Bush, M. B. (2017). The resilience of Amazonian forests. Nature, 541(7636), 167–168. https://doi.org/10.1038/541167a

Bush, M. B., & Oliveira, P. E. de. (2006). The rise and fall of the Refugial Hypothesis of Amazonian speciation: a paleoecological perspective. Biota Neotropica, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1590/s1676-06032006000100002

Bush, M.B., Gosling, W.D., Colinvaux, P.A. (2007). Climate change in the lowlands of the Amazon Basin. In: Tropical Rainforest Responses to Climatic Change. Springer Praxis Books. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-48842-2_3

Bush, M. B., P. Eduardo De-Oliveira, Colinvaux, P. A., Miller, M. C., & Joëlle Anne Moreno. (2004). Amazonian paleoecological histories: one hill, three watersheds. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 214(4), 359–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0031-0182(04)00401-8

Bush, M. B., & Silman, M. R. (2004). Observations on Late Pleistocene cooling and precipitation in the lowland Neotropics. Journal of Quaternary Science, 19(7), 677–684. https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs.883

Clapperton, C.M., 1993. Quaternary geology and geomorphology of South America. Elsevier, Amsterdam.

Colinvaux, P. A., De Oliveira, P. E., & Bush, M. B. (2000). Amazonian and neotropical plant communities on glacial time-scales: The failure of the aridity and refuge hypotheses. Quaternary Science Reviews, 19(1), 141–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-3791(99)00059-1

Cortes, A. L. A., Rapini, A., & Daniel, T. F. (2015). The Tetramerium lineage (Acanthaceae: Justicieae) does not support the Pleistocene Arc hypothesis for South American seasonally dry forests. American Journal of Botany, 102(6), 992–1007. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.1400558

Francisquini, M. I., Lorente, F. L., Ruiz Pessenda, L. C., Buso Junior, A. A., Mayle, F. E., Lisboa Cohen, M. C., França, M. C., Bendassolli, J. A., Fonseca Giannini, P. C., Schiavo, J., & Macario, K. (2020). Cold and humid Atlantic Rainforest during the last glacial maximum, northern Espírito Santo state, southeastern Brazil. Quaternary Science Reviews, 244, 106489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106489

Giovâni, P., Mota, G., & Frederico. (2021). Dung beetle β‐diversity across Brazilian tropical dry forests does not support the Pleistocene Arc hypothesis. Austral Ecology, 47(1), 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/aec.13080

Haffer, J. (1969). Speciation in Amazonian Forest Birds. Science, 165(3889), 131–137. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.165.3889.131

Haffer, J., & Prance, G. T. (2001). Climatic forcing of evolution in Amazonia during the Cenozoic: on the refuge theory of biotic differentiation. Amazoniana, 16(3), 579-607.

Häggi, C., Chiessi, C. M., Merkel, U., Mulitza, S., Prange, M., Schulz, M., & Schefuß, E. (2017). Response of the Amazon rainforest to late Pleistocene climate variability. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 479, 50–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2017.09.013

Huang, E., Yuan, Z., Wang, S., Yang, Y., Jia, G., & Tian, J. (2024). Expansion of grasslands across glacial Sundaland caused by enhanced precipitation seasonality. Quaternary Science Reviews, 337, 108824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2024.108824

Maslin, M. A., Ettwein, V. J., Boot, C. S., Bendle, J., & Pancost, R. D. (2012). Amazon Fan biomarker evidence against the Pleistocene rainforest refuge hypothesis? Journal of Quaternary Science, 27(5), 451–460. https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs.1567

Mayle, F. E., Beerling, D. J., Gosling, W. D., & Bush, M. B. (2004). Responses of Amazonian ecosystems to climatic and atmospheric carbon dioxide changes since the last glacial maximum. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 359(1443), 499–514. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2003.1434

McGee, D. (2020). Glacial–Interglacial Precipitation Changes. Annual Review of Marine Science, 12(1), 525–557. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-marine-010419-010859

Prado, D. E., & Gibbs, P. E. (1993). Patterns of Species Distributions in the Dry Seasonal Forests of South America. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 80(4), 902. https://doi.org/10.2307/2399937

Ray, N., & Adams, J. M. (2001). A GIS-based Vegetation Map of the World at the Last Glacial Maximum (25,000-15,000 BP). Internet Archaeology, 11. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.11.2