Picture this: it’s the tail end of the last ice age. The gargantuan ice sheets that cover Europe and North America are rapidly receding. It’s quickly become warmer than at any point in the previous hundred thousand years in the Northern Hemisphere, which has caused the ranges of plants and animals to change rapidly. Then, all of a sudden, the temperature plummets again. Cold-hardy plants and animals return to areas that they vacated over the previous few millennia and in certain places, the melting of the ice sheets halts or even reverses. It’s captivating to imagine, and this is exactly what happened during what’s known as the Younger Dryas.

If you know anything about the Pleistocene, you’ve definitely heard of it. In the natural sciences, the Younger Dryas refers to a period of major climate change which involved, among many other things, abrupt cooling in much of the globe starting around 12,900 years ago. As it came following a long trend of deglaciation and warming, it has often been referred to as a “return to ice-age conditions”. However, as we will see later in this post, this is somewhat of an oversimplification. It has also often been portrayed as being unique and/or unusually intense, either within the context of terminal Pleistocene climate shifts or the Quaternary as a whole; another notion to be evaluated here.

The Younger Dryas is one of the most heavily researched climatic events of the past. The causes of this cold reversal, as well as its exact severity and effects, have long been debated. Most theories support a large influx of freshwater into the ocean from melting ice sheets as the main or at least a major cause, which disrupted the thermohaline circulation and reduced heat transport to the Northern Hemisphere. However, there remains a fringe theory, apparently popular on the internet but largely rejected by science, which argues that an extraterrestrial impact was the actual trigger.

What were its (actual, not fictitious) causes? How similar was it to the other cold intervals of the last ice age? And what is the degree to which it can be described as extreme or anomalous?

A Cold Reversal

It was once believed that the end of the last ice age was a straightforward shift from intensely cold conditions to warm ones similar to today. However, it started to become clear that at some point in the midst of deglacial warming, much of the world suddenly became colder again. This is what happened between the Bølling–Allerød and Younger Dryas periods, which I will often abbreviate here as BA and YD, respectively.

Dryas octopetala, known by names such as mountain avens and white dryas, is a flower associated with Arctic and high-elevation areas. It thrives in cold climates and was widespread during glacial periods but retracted significantly during interglacials and interstadials. Although ice sheets started to retreat in Europe following the end of the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) between 25-18 thousand years ago, it remained cold enough for millennia that the plant was still common across large areas of Europe. This period of time between 18 and 14.7 thousand years ago was termed the “Oldest Dryas”.

During the Bølling–Allerød interstadial which started around 14,700 years ago, the Dryas plant became rare across most of Europe but then became common again starting about 12,900 years ago. Clay deposits lying above Allerød sediments contained fossils of the flower. This was more recent than both the Oldest Dryas and the Older Dryas (a short cold snap between the Bølling and Allerød warm periods when the plant was also widespread), which is what gives the “Younger Dryas” period its name.

But this wasn’t the only plant to become widespread again-a general influx of cold and dry-adapted vegetation partly regained dominance over Europe. Forests became sparser as steppe-tundra expanded, with the remaining trees trending towards more boreal forms. It was found that this return to cold conditions extended to the other side of the Atlantic as well, with the Midwestern and Northeastern United States and unglaciated sections of Canada showing clear signs of cooling.

However, it’s important to note before moving on that there is a distinction between the Younger Dryas chronozone, that is, the chronostratigraphic unit (or geologic time period) encompassing the interval from 12,900 to 11,700 years ago versus the Younger Dryas as a climatic event, i.e. the “Younger Dryas cooling”. This is because the two do not cleanly align over the entire world. Depending on the locale, climatic effects associated with the Younger Dryas may have had a delayed onset or earlier termination compared to those in Greenland where the ice core data has been collected from, or they may have even been absent altogether.

Since so much of the initial research on the Younger Dryas was focused on the areas most affected by cooling, which in order are Greenland, Europe, and the northern US/eastern Canada, it seemed fair to describe the Younger Dryas as an ice-age rerun. However, more analysis from other parts of the world has now indicated that the amplitude of cooling was in many regions mild or nonexistent, while other regions actually warmed (notably, Antarctica and a few other parts of the Southern Hemisphere).

As such, we’ll explore how the Younger Dryas compares to earlier cold intervals from a paleoclimatic and paleoenvironmental standpoint. But first, it is necessary to explore what may have caused it, as well as what definitely didn’t.

Trigger

The cause, or causes, of the Younger Dryas are still debated to this day. However, based on the scientific literature, one mechanism is nearly always considered to be involved to one degree or another: freshwater forcing. So what is it and what else do we know about it?

The Atlantic Ocean hosts a complex oceanic circulation system which transports warm water from the tropics to the mid and high latitudes off the coast of Europe, which is the fundamental reason why European winters are so much milder than would be expected for the latitude. This system, known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC for short, is part of the larger thermohaline circulation and has many facets that have far-reaching consequences beyond Europe.

The AMOC depends on a salinity-driven gradient to push warm waters northward, and if anything disrupts this gradient, the Earth’s climate state can be altered drastically. A large influx of freshwater can do precisely this, and this was a recurring feature of Earth’s climate cycles over the past few million years. During past ice ages, it often involved a large number of icebergs breaking off of the massive ice sheets and then melting in the Atlantic Ocean, but not in the case of the Younger Dryas.

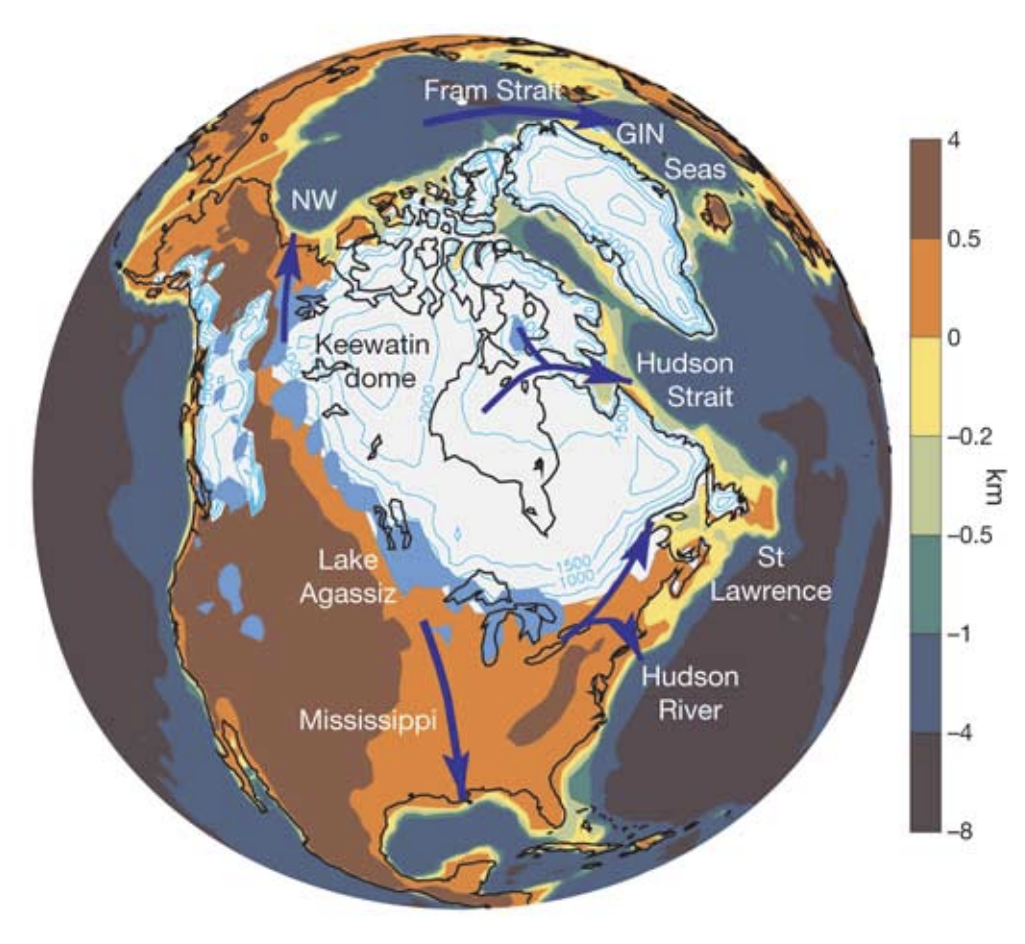

The influx of freshwater that may have triggered the Younger Dryas came not from icebergs as with Heinrich Events, but somewhere else. The North American Laurentide Ice Sheet was melting rapidly at the time. One popular hypothesis suggests that the flooding of Lake Agassiz, a large pro-glacial lake that formed at the edge of the Laurentide Ice Sheet in central Canada, caused water to surge eastwards into the Gulf of St. Lawrence which is part of the Atlantic.

Others have argued that the melting water from the Laurentide Ice Sheet instead went through a northern route, via the Mackenzie river and into the Arctic Ocean, and then used the Fram Strait to enter the seas northwest of Scandinavia. This means that the freshwater would have mostly bypassed the Atlantic itself, but since these northwestern seas are where North Atlantic Deep Water ultimately forms, this influx would certainly have been able to disrupt the AMOC anyway.

It’s not exactly confirmed yet which, if either, of these scenarios is correct but again, the fundamental mechanism for cooling is freshwater draining into the ocean and disrupting the AMOC. Still, some have argued that an injection of freshwater is not enough to explain the Younger Dryas. One paper by Renssen et al. (2015) argued that other mechanisms such as radiative forcing (involving decreased methane and nitrous oxide concentrations and increased dust levels) and changes in atmospheric circulation were also crucial components.

But not everyone is on board with normal, Earth-based processes being the trigger for this cold episode, with one scientifically-unsupported hypothesis claiming that an extraterrestrial impact was the real cause of the Younger Dryas cooling. This is known as the Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis (YDIH). A handful of authors argue that an asteroid may have struck somewhere in North America, with the impact causing massive, widespread wildfires and potentially destabilizing the Laurentide Ice Sheet.

The purported evidence for an impact includes charcoal left behind by the aforementioned massive fires, a layer of “black mat” dated to the Younger Dryas chronozone formed from the debris of the impact, geochemical anomalies such as increases in elements such as Iridium, detrimental impacts on human populations and megafauna, and-something we will explore in depth very soon-the “unusual abruptness and severity” of the Younger Dryas from a climatic standpoint.

But none of the claims hold up to scrutiny. There is no evidence of massive wildfires specific to the Younger Dryas interval; to the extent that there were fire peaks in certain areas during or near the YD, these could easily be explained by climate change and/or human-started fires. The black mats are not a consistent feature of the Younger Dryas strata and are not unique to it either, and their origins lie in normal geological processes.

There is no proof of an impact crater or meteoric fragments or debris. There was no surge in the abundance of specific chemicals that is high enough to be suggestive of meteoric impact. The Clovis people were not wiped out, they simply transitioned to a different lithic industry (Folsom). The most commonly suspected culprits for the disappearance of the American megafauna are humans and/or climate change (for an in-depth analysis of this, see this series of mine).

Moreover, there does not appear to be a consistent narrative put forth by the authors of the YDIH, which strongly challenges its credibility. They have at times claimed that a “supernova shockwave” was responsible for the creation of the Carolina Bays, while at other times claiming that a comet exploded and fractured over the Laurentide Ice Sheet in the area that is now the Great Lakes region, causing the numerous fragments to smash into the ice below.

So far, this hypothesis has basically nothing going for it. And as we will see in the very next section, the climatic effects of the Younger Dryas were not unique in terms of being unusually abrupt or intense either.

Alleged Uniqueness

The Younger Dryas has been frequently described as somehow being anomalous or extreme whether in the context of the last glacial-interglacial transition, the last glacial period, or perhaps even the Quaternary itself. This claim is not limited to those who ascribe an extraterrestrial impact as the cause of the event. But do these allegations of uniqueness really hold up? Let’s take a look at the evidence.

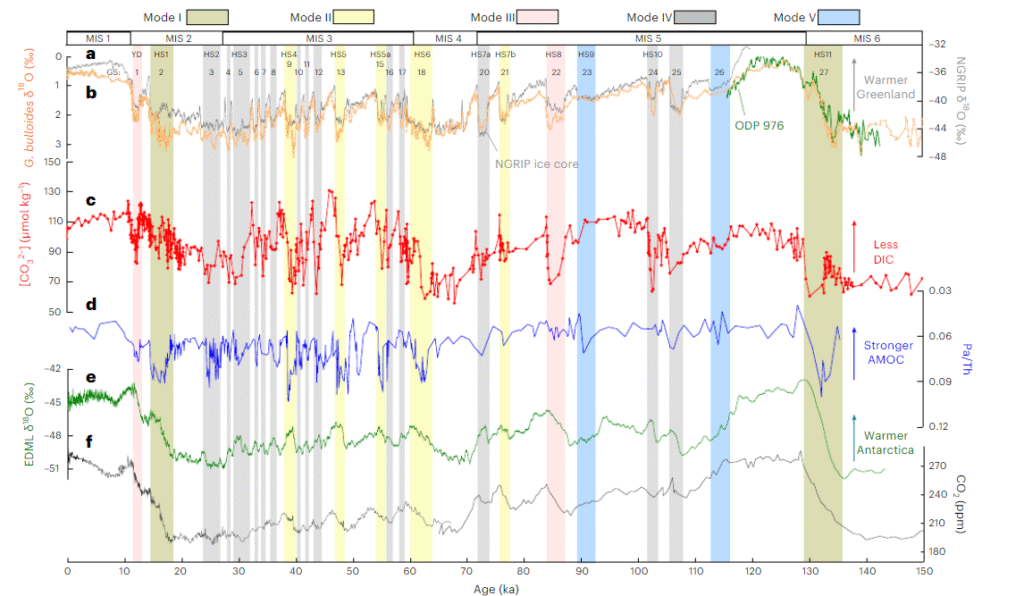

The more research we’ve conducted, the less distinct the Younger Dryas appears to be. It should quickly be noted that the onset of the Bølling–Allerød, specifically the early Bølling period, featured intense Northern Hemisphere warming that was no more extreme in magnitude than the cooling associated with the Younger Dryas. Further, statistical analysis by Nye and Condron (2021) indicates that the Bølling–Allerød to Younger Dryas shift was indistinguishable from the previous Dansgaard-Oeschger oscillations of the last glacial period.

Dansgaard-Oeschger (D-O) cycles occurred many times during the last glacial period; they were essentially rapid fluctuations between stadials and interstadials, with the exact causes being similarly unclear although changes in thermohaline circulation were likely somehow involved. If it’s true, as speculated in the previous section, that the Younger Dryas can’t be explained by freshwater forcing alone, then the implication is that the same may apply to the other stadials within D-O oscillations.

The analysis showed that the only real difference between the BA-YD transition and other D-O oscillations of the last climate cycle was that it occurred in the context of deglaciation whereas the previous ones occurred prior, usually at times when the baseline temperature of the globe was lower. But even with that small technical difference, there’s still a precedent.

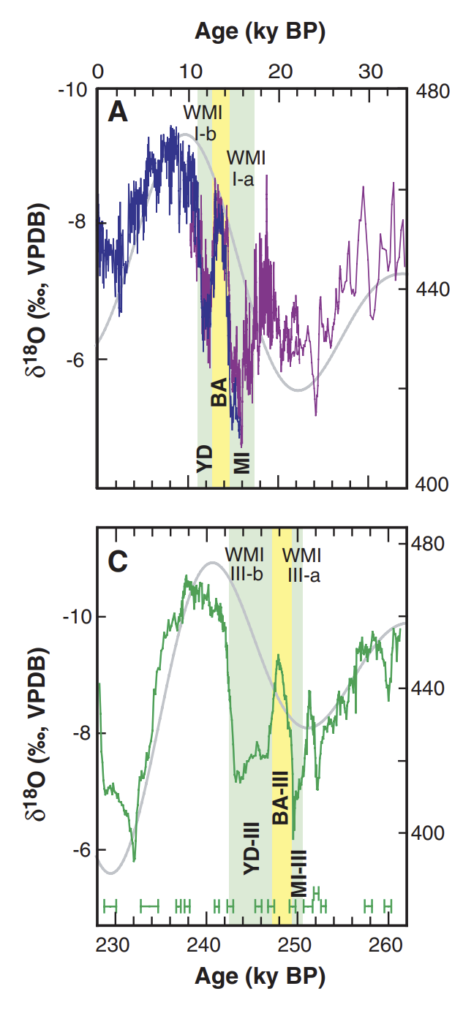

The Greenland ice cores only cover the last glacial period, but luckily, stalagmites from Chinese caves go much further back and cover previous glacial cycles as well. Stadials and interstadials are expressed as weak and strong monsoon periods in the stalagmites, respectively. And it was revealed that a shift comparable to the BA-YD transition occurred around 245 thousand years ago, as seen below.

So we’ve established that the notion of a “unique” Younger Dryas is not supported by the evidence. Then that leads us to ask: how intense was the Younger Dryas really? Can the Younger Dryas be accurately described as a “return to ice age conditions” in the sense of being as cold as the many other cold intervals of the last glacial period?

An important thing to note is that Greenland ice cores capture major climate events but do not faithfully reflect global temperature-they’re unsurprisingly heavily biased towards dynamics in the North Atlantic. Disruptions in the thermohaline circulation will cause a disproportionate cooling in that region, including Greenland, and therefore make D-O oscillations appear more violent than they were globally.

The GISP2 (Greenland Ice Sheet Project 2) core records an abrupt and extreme cooling associated with the Younger Dryas, which appears to be about as cold as the Last Glacial Maximum around 21 thousand years ago and colder than the Oldest Dryas between 18 and 15 thousand years ago. The newer, more accurate data from the NGRIP (North Greenland Ice Core Project) shows that the Younger Dryas was not as cold as the LGM or Oldest Dryas, but like all AMOC disruptions, the intensity of cooling is still exaggerated due to regional specifics.

As such, it’s necessary to look far beyond the North Atlantic realm, using a multitude of different sites to gain a more accurate picture. One study by Shakun and Carlson (2010) does this: it indicates that compared to the warmest part of the Holocene around 8 thousand years ago, the LGM was at a minimum 4.9°C colder while the Younger Dryas was only around 0.6°C colder. This means that the YD was only a fraction as cold as the LGM was. This is much less than would be suggested by the NGRIP and especially earlier GISP2 data.

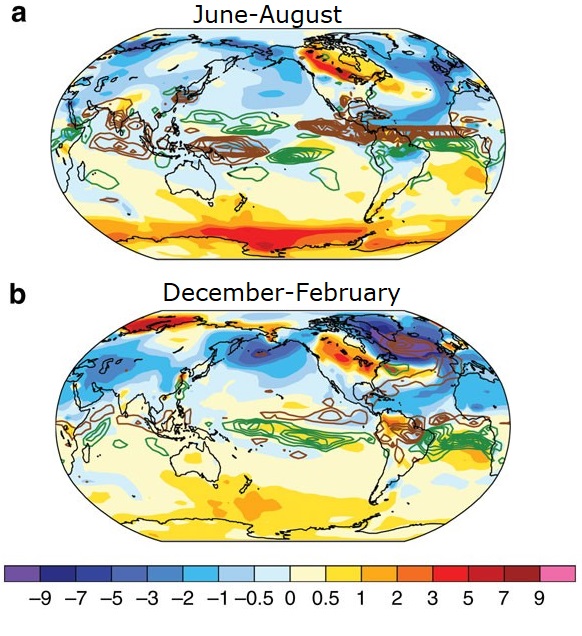

And this makes perfect sense. Ice sheets were much larger during the LGM than during the Younger Dryas and CO2 levels were far lower (185 ppm vs 240 ppm). The LGM was cold in both hemispheres, but the Younger Dryas actually featured slight warming of the Southern Hemisphere via the “bipolar seesaw” mechanism where thermohaline disruptions cause warming in one hemisphere and cooling in the other. Cooling in the Northern Hemisphere during the YD ultimately outweighed Southern Hemisphere warming, but it would still not be logical for the Younger Dryas to be as cold or nearly as cold as the LGM globally, contrary to what the Greenlandic ice cores alone would suggest.

Another important difference between the Younger Dryas and the LGM is that seasonality was greater during the Younger Dryas. The contrast between summer and winter temperatures was larger during the Younger Dryas than during the LGM as well as the present day. This can be attributed to orbital differences; summer insolation was higher and winter insolation was lower than during the LGM. Hence, much of the Northern Hemisphere actually had summers as warm or warmer than at present, paradoxically.

The graph above showing North Atlantic trends reveals that the Younger Dryas was not as cold as the Heinrich Stadials usually were in the Northern Hemisphere, while data from Antarctica reveals that it was actually among the warmest periods of the last glacial in the Southern Hemisphere. As such, we need to step away from thinking of the Younger Dryas as being a “return to ice age conditions” for the world as a whole, and think in more regional terms. So now let’s look at what happened, climatically and environmentally, from region to region.

Regional Impacts

Europe

Heat transport to the North Atlantic from the south was diminished, causing the expansion of sea ice. The sea ice was most extensive during winter, which meant that the ocean could not moderate temperatures during that season like it does today. This had powerful impacts not just on Greenland, as we already know, but also in Europe which is downwind of the North Atlantic. This resulted in very cold winters for the European continent, even as summers appear to have remained relatively warm. Growing seasons were shortened.

Precipitation was reduced alongside woody cover compared to the previous Bølling–Allerød period, and there was a resurgence of steppe-tundra vegetation in particular. However, the increase in vegetative openness was modest and Europe did not return to full ice age conditions akin to those of the LGM or the many Heinrich Stadials, and there were only limited glacial re-advances as summer warmth was sufficient to prevent the growth of ice over land.

Beringia

In Beringia (Alaska, the Yukon, and northeastern Siberia), there is no uniform signal for the Younger Dryas. Some sites do show local cooling and/or drying while others do not. Where cooling has been expressed, it was often mild, as in southern Alaska.

To the extent that cooling and/or drying occurred, this may not have been directly related to the effects of Atlantic circulation disruptions but rather independent atmospheric dynamics more specific to the Pacific. All in all, the Younger Dryas in this part of the world can be described as variable and relatively benign.

North America

In North America, the massive Laurentide Ice Sheet had been melting rapidly prior to the Younger Dryas. The rate of melt slowed during the Younger Dryas itself with multiple localized readvances, and then picked up pace once again following it. By this time, massive lakes had formed at the base of the Laurentide Ice Sheet from meltwater, such as the aforementioned Lake Agassiz in what’s now central Canada and Lake Chicago, the ancestor of Lake Michigan in the Great Lakes region.

To the west, the Cordilleran and Laurentide Ice Sheets had already become disconnected from each other, creating a corridor of dry land. Historically, it was thought that the ancestors of Native Americans had crossed this pathway to reach the contiguous United States. In recent times, however, many have been hypothesizing that the people had taken an earlier coastal route by hopping through ice-free islands along the Pacific Coast, which had been deglaciating for thousands of years prior to the YD.

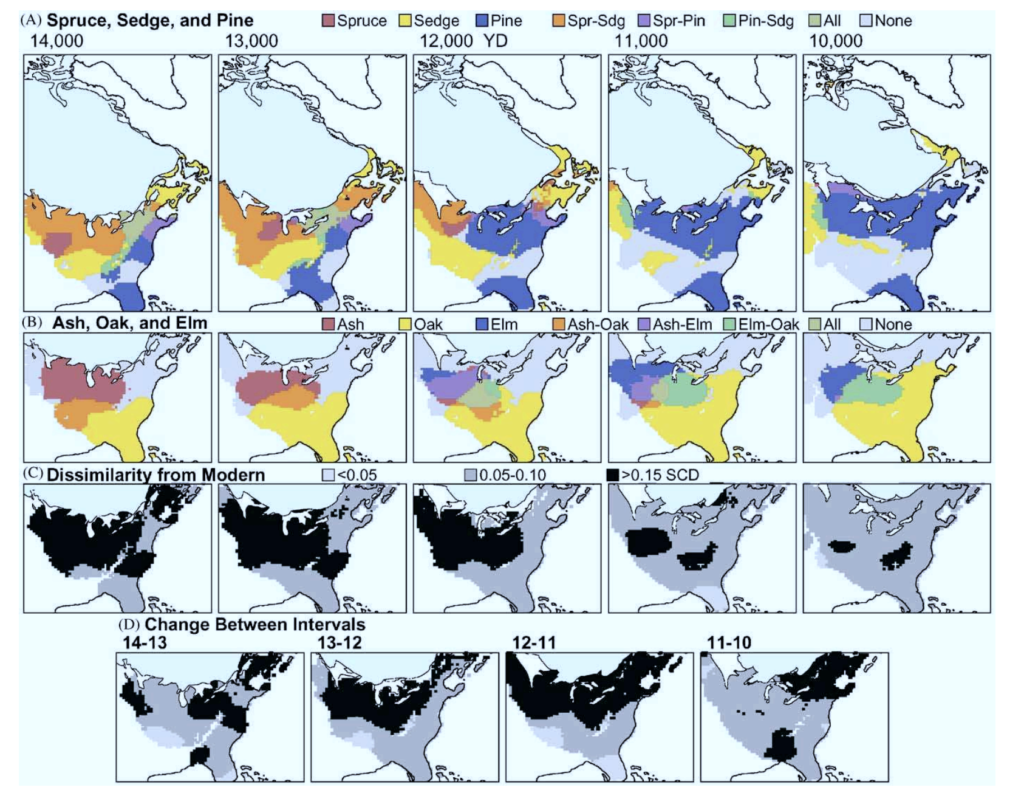

In unglaciated eastern North America, the Younger Dryas continued the trend of no-analog plant assemblages (plant communities without a modern counterpart) which started thousands of years earlier with the onset of deglaciation. Notable shifts in response to cooling took place in the Midwestern and Northeastern United States as well as southeastern Canada which were not far from the ice sheet. Here, pine percentages abruptly rise while Ash, a hardwood that became common during the B-A, declined. A study by Fastovich et al. (2020) suggests a cooling of about 1-2 degrees here compared to the preceding B-A on the basis of pollen and chemical analysis.

However, outside of the northern belt, the response to the YD in eastern North America ranged from minimal to nonexistent cooling or even, as in the southeast, gradual warming. Pollen data indicates that at Cupola Pond in the Missouri Ozarks, the Younger Dryas featured warming just as at White Pond in South Carolina and Browns Pond in Virginia.

Warming was most pronounced in Florida, with an expansion of southern pine forests over oak prairies. The Younger Dryas was similar in this regard to Heinrich Stadials in Florida as both ironically resulted in warmer and wetter conditions here, although the amplitude of vegetational change was not as strong in the former compared to the latter. The southeastern United States may have experienced wetter conditions during these periods due to a steepened temperature gradient between the waters along the east coast causing more storms to enter the region.

Moving west, in the southern Great Plains, Hall’s Cave in the Edwards Plateau of Texas records very little temperature fluctuation between the Bølling–Allerød and the Younger Dryas. The main difference between the two periods is in arboreal pollen. A pronounced drop in tree abundance took place as the environment shifted from a relatively closed woodland during the B-A to a more open woodland during the YD as precipitation dropped.

In the western continental United States, from the Pacific coast to the Rockies, we see a large degree of heterogeneity even in comparison to the eastern United States. Some mountainous areas saw limited glacial advances while others did not. Many sites appear to have had a wet early Younger Dryas and a dry late Younger Dryas. Overall, it seems that the southwest became somewhat wetter whereas the Pacific northwest became somewhat drier, a reversal of trends during the Bølling–Allerød warming. However, the wetting of the southwest was not to the same extent of that during Heinrich Stadial 1.

Low-Latitude and Monsoonal Regions

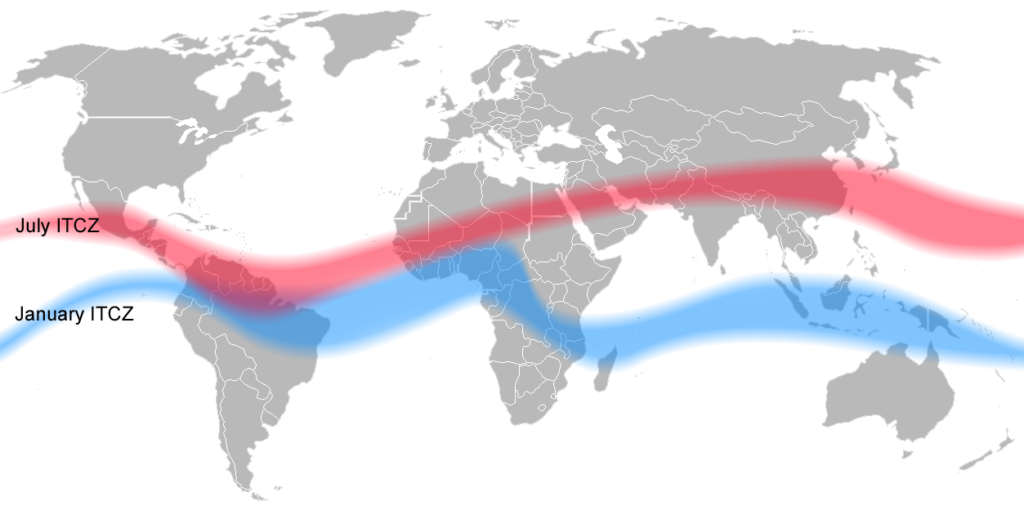

In lower latitude regions, the Younger Dryas appears to have started at nearly the same time as the North Atlantic but was slower to manifest fully, and its termination was also slower and earlier. In these parts of the world, there are often pronounced wet and dry seasons as opposed to large seasonal fluctuations in temperature, and hence the main effects of the Younger Dryas and similar centennial and millennial scale perturbations were on precipitation. Namely, some areas became wetter and others became drier, largely in accordance with shifts of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) which plays a crucial role in determining the intensity of monsoons over the regions where they occur.

The ITCZ is the area where the trade winds converge and it migrates seasonally tracking warmth, being located north of the equator during the Northern Hemisphere summer and south of the equator during the Southern Hemisphere summer. Thermal contrasts between the ocean and land cause it to migrate over land, which results in monsoons in the tropics and subtropics.

As it follows warmth, anything that upsets the balance of heat between the hemispheres or between land and sea can result in the ITCZ behaving differently, and hence weaker or stronger monsoons depending on the region. Multiple factors come together to determine how powerful monsoons are in a given place at a given time.

In China and India, enhanced monsoon activity occurs during times of high Northern Hemisphere summer insolation (which increases the thermal contrast between land and sea). The Younger Dryas was a period of high northern insolation, which would normally result in monsoons in India and China as strong or stronger than those of the present. However, Northern Hemisphere cooling due to AMOC weakening causes the ITCZ to shift south, and not penetrate the Asian landmass effectively. As a result, China and India both experienced weak monsoons during the Younger Dryas, albeit not as weak as during Heinrich Stadial 1 or many other stadials.

Likewise, North Africa was dry during the Younger Dryas as the West African monsoon weakened and penetrated less far north, in contrast to the previous Bølling–Allerød and succeeding early Holocene periods which were wetter. There was a Green Sahara period that followed the Younger Dryas in North Africa which was important for the establishment of agriculture in the region, as I’ve talked about in a previous article.

In the Neotropics meanwhile, there is evidence for similarly weak precipitation in northern South America and in Central America. At lake Peten Itza in Guatemala, wet, forested conditions were associated with the Last Glacial Maximum (which was cold but still featured a healthy AMOC) whereas dry, savannah-like conditions dominated during Heinrich Stadials. The Younger Dryas was, like the Heinrich Stadials, a time of relatively dry conditions but not to the same extent.

Meanwhile, precipitation increased to varying degrees in tropical South America south of the equator, with the most notable surge being in northeast Brazil. The southward shifting of the ITCZ caused a more intense and longer wet season over this region, which resulted in an expansion of moist forest elements in what was a savanna during the previous period. The climatic and environmental effects of the Younger Dryas were less pronounced than those of Heinrich Stadials, however.

Antarctica and Mid-Latitude Southern Hemisphere

Antarctica along with middle latitudes of the Southern Hemisphere from Patagonia to New Zealand experienced cooling and glacial re-advance in what’s known as the Antarctic Cold Reversal (ACR). It was contemporaneous with the Bølling–Allerød warming in the Northern Hemisphere, making the period from 14,700 to 12,900 BP the functional equivalent of the Younger Dryas in the Southern Hemisphere. During the Younger Dryas itself, Antarctica and other regions of the hemisphere warmed again. This is a classic bipolar seesaw dynamic resulting from shifts in the thermohaline circulation.

However, the extent of warming and/or cooling did not precisely mirror that which occurred in the Northern Hemisphere, as temperature shifts were milder. Additionally, warming in Antarctica lags cooling in Greenland by a few centuries, as in the case of the Younger Dryas. The end of the Younger Dryas also seems to have occurred sooner than in Greenland, in some ways similar to dynamics in the lower latitudes. Unlike the pronounced and widespread warming associated with Heinrich Stadial 1 in the Southern Hemisphere, the Younger Dryas was more variable and/or milder.

Summary of Changes

That was a lot of information to absorb at once, so let’s do a quick recap of what we talked about here in this article:

- The Younger Dryas was not cold enough to be described as a “return to glacial conditions” globally in the sense of being as cold as the LGM or the many stadials of the last glacial. At best, it can be described as a return to near glacial conditions in some regions.

- The abruptness and intensity of temperature change was not extreme in the context of D-O oscillations, with the main difference being that the BA-YD transition occurred in the context of deglaciation.

- The temperature change at the start of the preceding Bølling–Allerød was no less pronounced, it simply went in the opposite direction with warming as opposed to cooling.

- There was a precedent to the BA-YD transition during glacial termination III as recorded by Chinese stalagmites.

- As such, there is no reason to describe the Younger Dryas as anomalous and by extension, no reason to rely on an unusual cause to explain it such as an extraterrestrial impact, for which there is no evidence to begin with.

The changes that took place during the Younger Dryas were diverse and they varied in their intensity and directionality by region. However, an interesting prevailing theme here is that the Younger Dryas was largely expressed, both climatically and environmentally, as a weak version of a Heinrich Stadial. This makes sense as the fundamental cause is the same-a disruption of the AMOC due to freshwater forcing albeit to a smaller degree. Sometimes, the YD event is even referred to as “Heinrich Event 0” (H0).

The most important difference is that the YD did not involve a large discharge of icebergs but had a different pathway for freshwater to reach the North Atlantic. Further, as mentioned before, the Younger Dryas occurred during a warmer baseline of deglaciation, which made it warmer than the majority of Heinrich Stadials.

Despite the heavy study that’s been poured into understanding the Younger Dryas, it remains a topic of considerable debate and speculation. Still, we’ve made a substantial amount of progress in understanding the dynamics of this particular climatic event. Communicating these nuances clearly is important, as there will be less room for exaggeration or appeals to unsupported catastrophic explanations.

References

Bahr, A., Hoffmann, J., Schönfeld, J., Schmidt, M. W., Nürnberg, D., Batenburg, S. J., & Voigt, S. (2018). Low-latitude expressions of high-latitude forcing during Heinrich Stadial 1 and the Younger Dryas in northern South America. Global and Planetary Change, 160, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2017.11.008

Cheng, H., Edwards, R. L., Broecker, W. S., Denton, G. H., Kong, X., Wang, Y., Zhang, R., & Wang, X. (2009). Ice Age Terminations. Science, 326(5950), 248–252. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1177840

Cheng, H., Zhang, H., Spötl, C., Baker, J., Sinha, A., Li, H., Bartolomé, M., Moreno, A., Kathayat, G., Zhao, J., Dong, X., Li, Y., Ning, Y., Jia, X., Zong, B., Ait Brahim, Y., Pérez-Mejías, C., Cai, Y., Novello, V. F., & Cruz, F. W. (2020). Timing and structure of the Younger Dryas event and its underlying climate dynamics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(38), 23408–23417. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2007869117

Clark, P. U., Shakun, J. D., Baker, P. A., Bartlein, P. J., Brewer, S., Brook, E., Carlson, A. E., Cheng, H., Kaufman, D. S., Liu, Z., Marchitto, T. M., Mix, A. C., Morrill, C., Otto-Bliesner, B. L., Pahnke, K., Russell, J. M., Whitlock, C., Adkins, J. F., Blois, J. L., & Clark, J. (2012). Global climate evolution during the last deglaciation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(19), E1134–E1142. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1116619109

Cordova, C. E., & Johnson, W. C. (2019). An 18 ka to present pollen- and phytolith-based vegetation reconstruction from Hall’s Cave, south-central Texas, USA. Quaternary Research, 92(2), 497–518. https://doi.org/10.1017/qua.2019.17

Correa-Metrio, A., Bush, M. B., Cabrera, K. R., Sully, S., Brenner, M., Hodell, D. A., Escobar, J., & Guilderson, T. (2012). Rapid climate change and no-analog vegetation in lowland Central America during the last 86,000 years. Quaternary Science Reviews, 38, 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.01.025

Duprat-Oualid, F., Bégeot, C., Peyron, O., Rius, D., Millet, L., & Magny, M. (2022). High-frequency vegetation and climatic changes during the Lateglacial inferred from the Lapsou pollen record (Cantal, southern Massif Central, France). Quaternary International, 636, 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2022.04.012

Fastovich, D., Russell, J. M., Jackson, S. T., Krause, T. R., Marcott, S. A., & Williams, J. W. (2020). Spatial Fingerprint of Younger Dryas Cooling and Warming in Eastern North America. Geophysical Research Letters, 47(22). https://doi.org/10.1029/2020gl090031

Fu, M. (2023). Revisiting Western United States Hydroclimate During the Last Deglaciation. Geophysical Research Letters, 50(3). https://doi.org/10.1029/2022gl101997

Grimm, E. C., Watts, W. E., Jacobson, G., Hansen, B. C., Almquist, H., & Dieffenbacher-Krall, A. C. (2006). Evidence for warm wet Heinrich events in Florida. Quaternary Science Reviews, 25(17-18), 2197–2211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2006.04.008

Holliday, V. T., Daulton, T. L., Bartlein, P. J., Boslough, M. B., Breslawski, R. P., Fisher, A., Jorgeson, I., Scott, A. C., Koeberl, C., Marlon, J. R., Severinghaus, J. P., Petaev, M. I., & Claeys, P. (2023). Comprehensive refutation of the Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis (YDIH). Earth-Science Reviews, 104502–104502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2023.104502

Kneller, M., & Peteet, D. (1999). Late-Glacial to Early Holocene Climate Changes from a Central Appalachian Pollen and Macrofossil Record. Quaternary Research, 51(2), 133–147. https://doi.org/10.1006/qres.1998.2026

Kokorowski, H. D., Anderson, P. M., Mock, C. J., & Ложкин, А. В. (2008). A re-evaluation and spatial analysis of evidence for a Younger Dryas climatic reversal in Beringia. Quaternary Science Reviews, 27(17-18), 1710–1722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2008.06.010

Lesnek, A. J., Briner, J. P., Lindqvist, C., Baichtal, J. F., & Heaton, T. H. (2018). Deglaciation of the Pacific coastal corridor directly preceded the human colonization of the Americas. Science Advances, 4(5), eaar5040. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aar5040

Liu, X., Yang, H., Kang, S., Vandenberghe, J., Ai, L., Shi, Z., Cheng, P., Lan, J., Wang, X., & Sun, Y. (2022). Centennial-scale East Asian winter monsoon variability within the Younger Dryas. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 601, 111101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2022.111101

Liu, Z., Carlson, A. E., He, F., Brady, E. C., Otto-Bliesner, B. L., Briegleb, B. P., Wehrenberg, M., Clark, P. U., Wu, S., Cheng, J., Zhang, J., Noone, D., & Zhu, J. (2012). Younger Dryas cooling and the Greenland climate response to CO2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(28), 11101–11104. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1202183109

Mangerud, J. (2020). The discovery of the Younger Dryas, and comments on the current meaning and usage of the term. Boreas, 50(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/bor.12481

Meltzer, D. J., & Holliday, V. T. (2010). Would North American Paleoindians have Noticed Younger Dryas Age Climate Changes? Journal of World Prehistory, 23(1), 1–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10963-009-9032-4

Novello, V. F., Cruz, F. W., Vuille, M., Stríkis, N. M., Edwards, R. L., Cheng, H., Emerick, S., de Paula, M. S., Li, X., Barreto, E. de S., Karmann, I., & Santos, R. V. (2017). A high-resolution history of the South American Monsoon from Last Glacial Maximum to the Holocene. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 44267. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44267

Nye, H., & Condron, A. (2021). Assessing the statistical uniqueness of the Younger Dryas: a robust multivariate analysis. Climate of the Past, 17(3), 1409–1421. https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-17-1409-2021

Partin, J. W., Quinn, T. M., Shen, C.-C. ., Okumura, Y., Cardenas, M. B., Siringan, F. P., Banner, J. L., Lin, K., Hu, H.-M. ., & Taylor, F. W. (2015). Gradual onset and recovery of the Younger Dryas abrupt climate event in the tropics. Nature Communications, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms9061

Pedro, J. B., Bostock, H. C., Bitz, C. M., He, F., Vandergoes, M. J., Steig, E. J., Chase, B. M., Krause, C. E., Rasmussen, S. O., Markle, B. R., & Cortese, G. (2015). The spatial extent and dynamics of the Antarctic Cold Reversal. Nature Geoscience, 9(1), 51–55. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2580

Piacsek, P., Behling, H., Ballalai, J. M., Nogueira, J., Venancio, I. M., & Albuquerque, A. L. S. (2021). Reconstruction of vegetation and low latitude ocean-atmosphere dynamics of the past 130 kyr, based on South American montane pollen types. Global and Planetary Change, 201, 103477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2021.103477

Pinter, N., Scott, A. C., Daulton, T. L., Podoll, A., Koeberl, C., Anderson, R. S., & Ishman, S. E. (2011). The Younger Dryas impact hypothesis: A requiem. Earth-Science Reviews, 106(3-4), 247–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2011.02.005

Renssen, H., Mairesse, A., Goosse, H., Mathiot, P., Heiri, O., Roche, D. M., Nisancioglu, K. H., & Valdes, P. J. (2015). Multiple causes of the Younger Dryas cold period. Nature Geoscience, 8(12), 946–949. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2557

Shakun, J. D., & Carlson, A. E. (2010). A global perspective on Last Glacial Maximum to Holocene climate change. Quaternary Science Reviews, 29(15-16), 1801–1816. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.03.016

Shuman, B. (2002). The anatomy of a climatic oscillation: vegetation change in eastern North America during the Younger Dryas chronozone. Quaternary Science Reviews, 21(16-17), 1777–1791. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-3791(02)00030-6

Sonu Jaglan, Gupta, A. K., Clemens, S. C., Dutt, S., Cheng, H., & Singh, R. K. (2021). Abrupt Indian summer monsoon shifts aligned with Heinrich events and D-O cycles since MIS 3. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 583, 110658–110658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2021.110658

Stokes, Ch. R. (2017). Deglaciation of the Laurentide Ice Sheet from the Last Glacial Maximum. Cuadernos de Investigación Geográfica, 43(2), 377. https://doi.org/10.18172/cig.3237

Tarasov, L., & Peltier, W. R. (2005). Arctic freshwater forcing of the Younger Dryas cold reversal. Nature, 435(7042), 662–665. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03617

Wilcox, P. S., Fowell, S. J., & Baichtal, J. F. (2020). A mild Younger Dryas recorded in southeastern Alaska. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research, 52(1), 236–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/15230430.2020.1760504

Wilcox, P. S., & Fu, M. (2025). Minimal AMOC Impact in Alaska During the Younger Dryas. Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology, 40(12). https://doi.org/10.1029/2025pa005324

Yu, J., Anderson, R. F., Jin, Z. D., Ji, X., Thornalley, D. J. R., Wu, L., Thouveny, N., Cai, Y., Tan, L., Zhang, F., Menviel, L., Tian, J., Xie, X., Rohling, E. J., & McManus, J. F. (2023). Millennial atmospheric CO2 changes linked to ocean ventilation modes over past 150,000 years. Nature Geoscience, 16(12), 1166–1173. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-023-01297-x