One of the most contentious debates in all of archeology is when and how the Americas were first settled. For a while, it was claimed that the first people in the Americas were the “Clovis”. They were a group of big-game hunters with distinctive hunting tools that allegedly bypassed formidable glaciers through an inland ice-free corridor and spread across North America no earlier than about 13,000 years BP(before present). However, the idea of the Clovis as the first arrivals to the New World has been called into question by archeologists for decades. Evidence also suggests that a coastal Pacific route, instead of an inland one, may have been used by the ancestors of Native Americans to get past the massive ice sheets and reach warmer latitudes.

Anyone familiar with controversies surrounding the settlement of the Americas at the very end of the Pleistocene may already be aware of the pre-Clovis and coastal route hypotheses. However, I would like to provide a detailed and engaging description of what I consider to be the most likely settlement process from start to finish, as well as address the possibility of even earlier habitation. Since there is still a lot that scientists are uncertain about regarding this topic, this piece will include some reasonable speculation based on the best information we have from genetics and archeology.

With that said, let’s get to it.

Chilling in the Arctic

Many people with a passing knowledge of history have already heard that the ancestors of Native Americans migrated from Asia to America using a land bridge during the ice age, but the specifics of how this happened are a lot more complex and, in my opinion, much more fascinating.

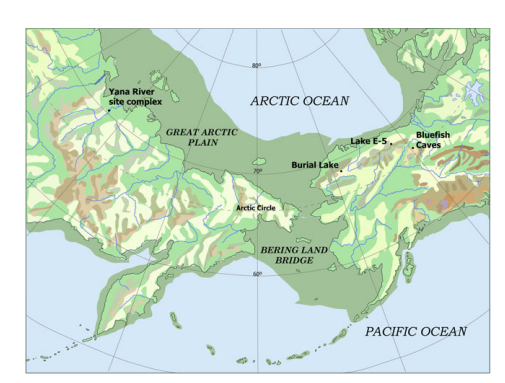

The story begins in the Arctic, or specifically in Arctic Beringia. Beringia is a region stretching from the Lena river in Siberia to the Mackenzie river in Canada and spans both the Arctic and subarctic latitudes. It is bound by the Arctic Ocean to the north and the Bering Sea to the south. The turbulent, cold waters of the Bering strait separate Alaska and eastern Russia today, but during ice ages, this area formed a land bridge as sea levels dropped and dry land was exposed. It was therefore possible for plants, animals, and humans to move between the Old World and the New.

Prior to the height of the ice age, also known as the Last Glacial Maximum(LGM), a population related to Ancestral North Eurasians mixed with Ancient Northern East Asians in Siberia to form a group known as Ancient Paleo-Siberians1. The Ancient Paleo-Siberians(APS) migrated northeast into a part of Siberian Beringia known as the Great Arctic Plain(GAP). This was a very cold and dry region but it was covered in a vast expanse of grassy steppe-tundra and hosted lots of big game which attracted humans. The large game would be critical for people living at this latitude where plant foods were hard to come by.

At some point near the LGM, some of the APS split off to form a new group called Ancient Native Americans(ANA) and moved southeastwards into now-submerged land known as the Bering Land Bridge(BLB). This subarctic region is more or less synonymous with the “Beringian buckle” that paleobiologist R. Dale Guthrie has written about: a distinctive wet region wedged between drier steppe-tundra to its west and east2. Due to being adjacent to the Bering Sea, it received relatively high cloud-cover and precipitation and was poorly drained due to its low elevation. This resulted in a shrubby landscape which may have lacked the large herds of animals that were present in the grassy GAP region1.

The BLB is the most likely hub of the ANA population during the so-called “Beringian standstill”, a hypothesized period of time during which the ancestors of Native Americans remained isolated in the far north for a few thousand years as the North American ice sheet blocked their movement to the east and south. A reliance on aquatic resources was probably necessary to survive here and they may have developed some form of watercraft as a result. The lack of large game and maritime-lifestyle could have resulted in microblade technology-used for big-game hunting-being temporarily lost1.

However, things would soon change. The Arctic and subarctic became warmer, and the ice started to melt as part of end-Pleistocene deglaciation. The people living in Beringia, no longer trapped, would move into the temperate and tropical latitudes of the Americas, eventually giving rise to an enormous number of cultures from the southern tip of South America to Greenland who we now call the First Nations or indigenous Americans.

A Coastal Migration

With the bitter cold losing its grip, the stage was now set for a full-on colonization of the Americas. The human settlers of the terminal Pleistocene Americas are referred to as “Paleo-Indians”. For a while, it was believed that the “Clovis” people were the first representatives of the Paleo-Indians and used an opening between the Cordilleran and Laurentide Ice Sheet to colonize North America around 13k(13 thousand) years ago. This is known as the Clovis-first theory3. Yet, the theory has major issues and has largely been abandoned by archeologists in the present day.

We have strong evidence that humans were in the Americas prior to 13k years ago with many sites likely dating from 14 to 16 thousand years old3 4. Not only do these sites predate Clovis, they also predate the opening of the interior ice free corridor between the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets in Canada that would have allowed humans to enter what is now the contiguous United States.

How did people reach America if not through this corridor? There is another hypothesis that has been around for a while and is increasingly better supported, which is that rather than following a path between the two ice sheets as it opened up, the Paleo-Indians moved along the coast which deglaciated sooner and left a route open around 17k years ago1. The BLB would have been the launchpad for this migration. Boats, along with a kelp-forest highway, are speculated to have facilitated travel along the coast5.

Lending credence to the coastal migration and pre-Clovis hypothesis are genetic studies. Analysis on Native American genomes indicates a diversification of mitochondrial lineages around 16k years ago likely coinciding with their arrival in the Pacific Northwest6. Genetic testing on a 10k year old Native American dog in Alaska indicates that the lineage split from Siberian dogs 16,700 years ago4. The landfall of Paleo-Indians into the Pacific Northwest would’ve happened slightly before the diversification of their mitochondrial lineages but probably slightly after their dogs split from Siberian dogs. Therefore, we can say that the arrival of Paleo-Indians to mainland North America most likely took place somewhere between 16 and 16.7k years ago.

It is worth noting that archeological evidence indicates very old sites along the entire coast of the Americas, with Monte Verde in Chile reliably dated to 14,500 years BP3. Although dated to 14,500 years BP, the arrival of Paleo-Indians to this region most certainly predates this by at least a few centuries since the coast at the time has now been submerged due to sea level rise, meaning the area they made landfall in is now under water and cannot be found. Archeological sites frequently postdate the first arrival of humans to an area.

A rapid colonization of the Pacific coast would prove Paleo-Indians were effective sailors. However, they were evidently rapidly traversing east across land as well. Sites in eastern North and South America date to between 14k years ago and older3. The varied geography of the these two massive continents-deserts, mountains, forests-was seemingly not a barrier to their dispersal.

Despite having moved into temperate, subtropical, and tropical latitudes, the indigenous peoples of the Americas retain the “Arctic signal” in the form of genetic adaptations to life at high latitudes in Beringia. Examples include a group of genes known as FADS which are advantageous for metabolizing protein and fat-rich diets, as well as the EDAR gene which may have helped increase vitamin D in breast milk for infants in the low UV Arctic and Subarctic environments7 8. These are found in very high frequency across all Native American populations regardless of current diet and location, indicating a recent Arctic origin.

Post-Colonization Splits

Although an Arctic past of native populations is well-established, it is not entirely clear how all of these populations are related to each other and whether or not some are descendants of multiple waves of migrations. Raghavan et al. 9 believe that speakers of Athabaskan languages share all their ancestry with Central and South Americans. Skoglund and Reich10 disagree and argue that there were three migrations from Asia: one “First American” stream that Central and South American natives belong to, another source that gave rise to Eskimo-Aleut speakers, and another that accounts for about 10% of the ancestry of Athabaskan speakers. The issue remains unresolved for now.

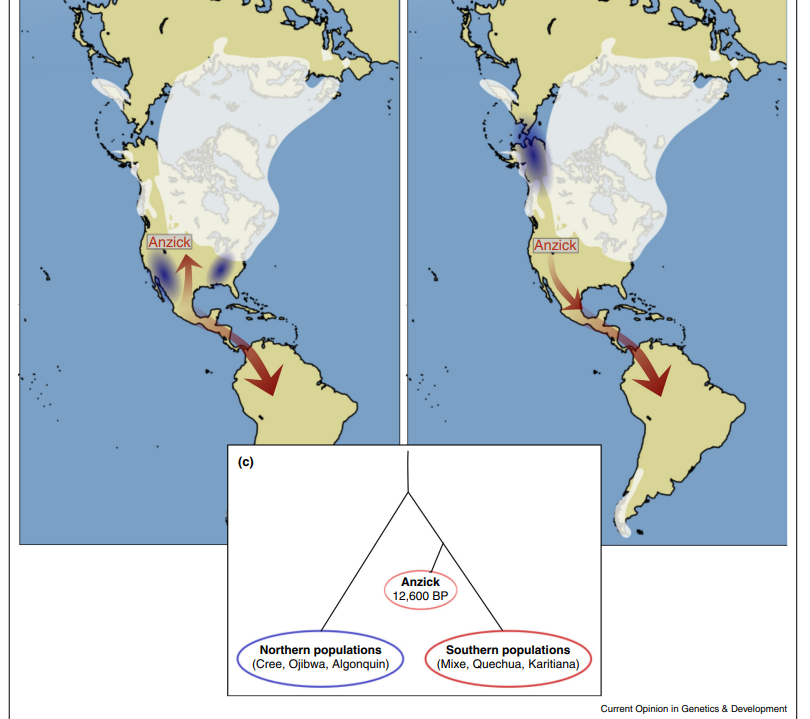

Still, it seems that the most significant split in Native American populations is between southern and northern populations. The southern populations are represented by South and Central Americans(Mixe, Quechua, Yaghuan) and the latter by Northern North Americans(Cree, Ojibwe, Algonquin). This split likely dates back to 12,600 years ago or earlier11.

The remains of a child discovered in western Montana, called Anzick-1, dates to around that time and was associated with the big-game hunting Clovis. Surprisingly, the genome of the individual was found to harbor a strong affinity for the southern clade of Native Americans rather than the northern one in spite of its geographic location.

This could suggest one of two things: since Clovis artifacts initially appear in southern North America, Anzick-1 in northern North America could represent a migration of this southern population into the territory of Northern Native Americans where they introduced Clovis technology, but northern populations later experienced a resurgence and displaced them.

Alternatively, Anzick-1 could represent the original genome of all Paleo-Indians south of the ice sheets while northern populations remained stuck in Beringia until the inland ice-free corridor emerged, causing the northern population to replace the original Anzick-like population of northern North America around 12,600 years ago. This raises the possibility that it was not one or the other ice-free route that was utilized, but potentially both at separate times by separate groups.

Human habitation south of the ice during and before the LGM?

A number of archeological sites south of the erstwhile North American ice sheet which allegedly date to the time of the LGM roughly 18 to 22k years ago or older have drawn great interest but remain very controversial. This includes the White Sands footprints in New Mexico and some sites in Brazil12 13. There is considerable back-and-forth debate regarding White Sands in particular14 15. A study from earlier this year provided evidence of butchery of a giant extinct relative of the armadillo in Argentina which was dated to 21k years ago16, but as this study is new, we can probably expect that the dating will be challenged in the future.

Radiocarbon dating can be wrong for any number of reasons but given how much the debate seems to swing back and forth regarding the purported early dates of these sites or their archeological validity as a whole, I will not outright dismiss them. However, if they happen to be genuine, they would represent an incursion of human beings into the Americas that clearly predates what mitochondrial DNA tells us about Paleo-Indian history. That in turn implies one of two possibilities.

The first is that the estimates for Paleo-Indian arrival based on genomics is wrong. Different methodologies can result in different estimates in science, some more accurate than others, so this is possible. However, there was no ice-free corridor during the LGM 18-22k years ago so whoever was present during that time-assuming they came from northeast Siberia-would have needed to have arrived thousands of years earlier. That would suggest that the estimate of first people arrival in the Pacific Northwest from the molecular clock was off by not by a few thousand years but several thousand years, which I think is unlikely. Additionally, we know that the Ancient Native Americans only split from the Ancient Paleo-Siberians no earlier than 24 thousand years ago.

This leads to the other possibility, which is that these arrivals represented an earlier wave of people who were genetically distinct from the ANA descended Paleo-Indians which arrived later and either went extinct or left minimal ancestry in present native populations. The first settlement of the Arctic was the Yana rhinoceros site in Siberia dated to around 32k years ago17. Did a human population living in eastern Siberia prior to the LGM make a sudden dash eastwards and bypass the ice sheet somehow? Or could it be that these alleged early arrivals came from a different route altogether?

A mysterious affinity towards Australasian populations-Papuans, Australian aborigines, Andamanese-was found in indigenous groups in the Amazon11, and according to another study, in the Pacific coast of South America as well18. This Australasian-like ancestry was named “Population-Y” and it sparked theories about a possible wave of Australasian settlement in the Americas which may have taken place during or before the LGM. However, Australasian-like ancestry was not uncommon in Asia tens of thousands of years ago, and it is far more likely that this Population-Y ancestry simply reflects descent from a lineage in substructured northeastern Asia which retained greater Australasian affinity than other lineages before migrating10.

The question, then, is whether this lineage migrated earlier than the 16k year old Paleo-Indian wave. It is important to realize that genetic testing shows a great deal of variation in the strength of the Australasian signal even within South American native populations18. Therefore, I do not think it is far fetched to believe that there was simply variation in Australasian affinity among Paleo-Indians who settled the Americas, with the branch that pushed south into South America possessing a signal while those who settled areas further north had none.

In other words, despite what you may or may not have been told, there is currently not much concrete evidence for a wave of ancestry or settlement which predates the known Paleo-Indians arrival after the LGM. It is inconclusive along the paleogeographic, genetic, and archeological fronts. It would be very helpful if we could retrieve human DNA samples from some of the purported LGM or pre-LGM sites, as this would shed enormous light on who, if anyone, was present in the Americas at the time. My guess is that this won’t happen and the Paleo-Indians do indeed represent the earliest arrival of humans to the Americas, but I would be elated if it turns out that I’m wrong on this.

Summary and Concluding Remarks

To summarize, a population of mixed Eurasian ancestry(APS) migrated to the Great Arctic Plain(GAP) of northeastern Siberia and then to the now submerged Bering Land Bridge(BLB) and gave rise to a new population ancestral to Native Americans(ANA). All of this is happening within the broader region known as Beringia. As the ice started to melt, they likely went down the coast of the Pacific until they landed in the Pacific Northwest region around 16 thousand years ago. Afterwards, they continued to sail down the coast as well as moved eastwards to settle the Americas. All Native American populations today carry the genetic signature of an Arctic origin.

The initial colonization precedes the Clovis culture. The northern elements of the Clovis like Anzick-1 may represent either a southern expansion into the northern contiguous US or the descendants of the original settlers who were displaced by a second group of migrants from Beringia. The total number of migrations from Asia is not clear, but it is thought that Eskimo-Aleuts and Athabaskan speakers may harbor ancestry from more recent migrations to the Americas as well. Potential evidence for LGM or pre-LGM habitation of the Americas is intriguing but insufficient.

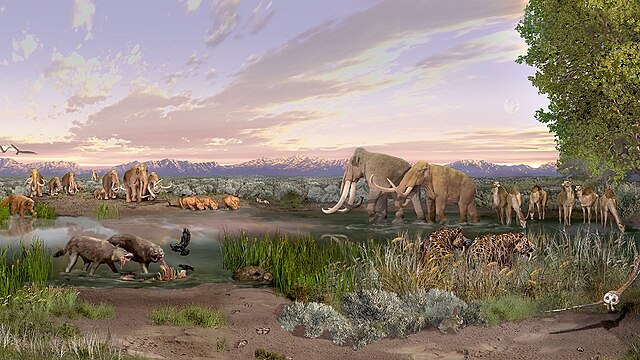

Of course, science is always revising itself and any number of things written here could turn out to be wrong in the future but this is a good attempt to string together the available data to produce the most likely scenario of the peopling of the New World. I definitely plan on writing more about the prehistory of the Americas. Specifically, I’ll be talking about the megafaunal extinctions which took place following the arrival of people and try to determine the relative role of humans and climate in them.

References

1. Hoffecker, J. F., Elias, S. A., Scott, G. R., O’Rourke, D. H., Hlusko, L. J., Potapova, O., Pitulko, V., Pavlova, E., Bourgeon, L., & Vachula, R. S. (2023). Beringia and the peopling of the Western Hemisphere. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 290(1990). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2022.2246

2. Guthrie, R. D. (2001). Origin and causes of the mammoth steppe: a story of cloud cover, woolly mammal tooth pits, buckles, and inside-out Beringia. Quaternary Science Reviews, 20(1-3), 549–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-3791(00)00099-8

3. Dillehay, T. D., Ocampo, C., Saavedra, J., Sawakuchi, A. O., Vega, R. M., Pino, M., Collins, M. B., Scott Cummings, L., Arregui, I., Villagran, X. S., Hartmann, G. A., Mella, M., González, A., & Dix, G. (2015). New Archaeological Evidence for an Early Human Presence at Monte Verde, Chile. PLOS ONE, 10(11), e0141923. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0141923

4. Da Silva Coelho, F. A., Gill, S., Tomlin, C. M., Heaton, T. H., & Lindqvist, C. (2021). An early dog from southeast Alaska supports a coastal route for the first dog migration into the Americas. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 288(1945), 20203103. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2020.3103

5. Erlandson, J. M., Graham, M. H., Bourque, B. J., Corbett, D., Estes, J. A., & Steneck, R. S. (2007). The Kelp Highway Hypothesis: Marine Ecology, the Coastal Migration Theory, and the Peopling of the Americas. The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology, 2(2), 161–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564890701628612

6. Llamas, B., Fehren-Schmitz, L., Valverde, G., Soubrier, J., Mallick, S., Rohland, N., Nordenfelt, S., Valdiosera, C., Richards, S. M., Rohrlach, A., Romero, M. I. B., Espinoza, I. F., Cagigao, E. T., Jiménez, L. W., Makowski, K., Reyna, I. S. L., Lory, J. M., Torrez, J. A. B., Rivera, M. A., & Burger, R. L. (2016). Ancient mitochondrial DNA provides high-resolution time scale of the peopling of the Americas. Science Advances, 2(4), e1501385. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1501385

7. Amorim, C. E., Nunes, K., Meyer, D., Comas, D., Bortolini, M. C., Salzano, F. M., & Hünemeier, T. (2017). Genetic signature of natural selection in first Americans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114(9), 2195–2199. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1620541114

8. Hlusko, L. J., Carlson, J. P., Chaplin, G., Elias, S. A., Hoffecker, J. F., Huffman, M., Jablonski, N. G., Monson, T. A., O’Rourke, D. H., Pilloud, M. A., & G. Richard Scott. (2018). Environmental selection during the last ice age on the mother-to-infant transmission of vitamin D and fatty acids through breast milk. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(19). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1711788115

9. Raghavan, M., DeGiorgio, M., Albrechtsen, A., Moltke, I., Skoglund, P., Korneliussen, T. S., Grønnow, B., Appelt, M., Gulløv, H. C., Friesen, T. M., Fitzhugh, W., Malmström, H., Rasmussen, S., Olsen, J., Melchior, L., Fuller, B. T., Fahrni, S. M., Stafford, T., Grimes, V., & Renouf, M. A. P. (2014). The genetic prehistory of the New World Arctic. Science, 345(6200). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1255832

10. Skoglund, P., & Reich, D. (2016). A genomic view of the peopling of the Americas. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development, 41, 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gde.2016.06.016

11. Skoglund, P., Mallick, S., Bortolini, M. C., Chennagiri, N., Hünemeier, T., Petzl-Erler, M. L., Salzano, F. M., Patterson, N., & Reich, D. (2015). Genetic evidence for two founding populations of the Americas. Nature, 525(7567), 104–108. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14895

12. Bennett, M. R., Bustos, D., Pigati, J. S., Springer, K. B., Urban, T. M., Holliday, V. T., Reynolds, S. C., Budka, M., Honke, J. S., Hudson, A. M., Fenerty, B., Connelly, C., Martinez, P. J., Santucci, V. L., & Odess, D. (2021). Evidence of humans in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum. Science, 373(6562), 1528–1531. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abg7586

13. Coutouly, Y. A. G. (2021). Questioning the Anthropic Nature of Pedra Furada and the Piauí Sites. PaleoAmerica, 8(1), 29–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/20555563.2021.1943181

14. Pigati, J. S., Springer, K. B., Honke, J. S., Wahl, D. B., Champagne, M., Zimmerman, S., Gray, H. J., Santucci, V., Odess, D., Bustos, D., & Bennett, M. R. (2023). Independent age estimates resolve the controversy of ancient human footprints at White Sands. PubMed, 382(6666), 73–75. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adh5007

15. Rhode, D., Neudorf, C. M., Rachal, D., Davis, L. G., Madsen, D. B., & Dello-Russo, R. (2024). Unresolved: Persistent Problems with the White Sands Locality 2 Geochronology. PaleoAmerica, 10(1), 10–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/20555563.2024.2345979

16. Del Papa, M., De Los Reyes, M., Poiré, D. G., Rascovan, N., Jofré, G., & Delgado, M. (2024). Anthropic cut marks in extinct megafauna bones from the Pampean Region (Argentina) at the last glacial maximum. PLOS ONE, 19(7). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0304956

17. Pitulko, V. V. (2004). The Yana RHS Site: Humans in the Arctic Before the Last Glacial Maximum. Science, 303(5654), 52–56. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1085219

18. Silva, M. A. C. E., Ferraz, T., Bortolini, M. C., Comas, D., & Hünemeier, T. (2021). Deep genetic affinity between coastal Pacific and Amazonian natives evidenced by Australasian ancestry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(14). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2025739118