The very last population of woolly mammoths in the world survived on a small tundra island in northeast Siberia until only about 4,000 years ago, when the Egyptian pyramids were being built. They outlasted their cousins on the mainland by thousands of years, and have been the subject of intense research and intrigue.

This remote redoubt of the last mammoths is known as Wrangel Island, today home to a large seasonal population of polar bears. Theories for the demise of the mammoths here include everything from genomic meltdown from inbreeding, disease, natural disaster, climate change, or humans. Recently a study has argued that a random, non-human related event killed off the inbred but otherwise healthy and stable mammoth population1.

While it’s fascinating that woolly mammoths survived so late and it’s understandable that people are interested in what caused this specific population to die out, it’s not all that relevant in the context of determining what happened to the species as a whole as many people seem to think it is. It’s already well-known in biology that island populations are far more susceptible to extinction from random catastrophes than their counterparts on the mainland. Indeed, some researchers caution against extrapolating from the Wrangel mammoths to mainland ones and say it’s still largely a question of climate change vs. humans for the latter2 3.

Regarding climate vs. humans, it’s hard for me to believe that humans weren’t at least partly responsible for the extinction of the species as a whole. Climate change may have caused woolly mammoths to retreat from the vast majority of their glacial range in Eurasia and North America but it doesn’t explain everything. The fact that the last two woolly mammoth populations were those of Wrangel and St. Paul off the coast of Alaska, two islands which are mostly unremarkable except for their remoteness, raises the question of why mammoths survived there and not the climatically identical mainland nearby.

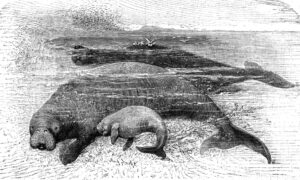

Speaking of how isolated populations can mislead when it comes to extinction, there’s a somewhat similar case with Stellar’s sea cows. These relatives of the Dugong were once common in the north Pacific but vanished across most of its range during the Pleistocene before finally going extinct in the 18th century. Researchers sampled a Stellar’s sea cow from the Commander islands and concluded that the species was long doomed to extinction from inbreeding4 only for other researchers to point out that the Commander island subspecies became isolated very long ago and likely wasn’t representative of the species as a whole5. Genomes from Stellar cows from other parts of the Pacific will shed more light on the subject, but this shows how important it is to keep context in mind when discussing extinction.

References

1. Dehasque, M., Morales, H. E., Díez-del-Molino, D., Patrícia Pečnerová, J. Camilo Chacón-Duque, Foteini Kanellidou, Muller, H., Plotnikov, V., Protopopov, A., Tikhonov, A., Pavel Nikolskiy, Danilov, G. K., Maddalena Giannì, Laura, Higham, T., Heintzman, P. D., Nikolay Oskolkov, Gilbert, T. P., Anders Götherström, & Tom. (2024). Temporal dynamics of woolly mammoth genome erosion prior to extinction. Cell. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2024.05.033

2. Fordham, D. A., Brown, S. C., Akçakaya, H. R., Brook, B. W., Haythorne, S., Manica, A., Shoemaker, K. T., Austin, J. J., Blonder, B., Pilowsky, J., Rahbek, C., & Nogues‐Bravo, D. (2021). Process‐explicit models reveal pathway to extinction for woolly mammoth using pattern‐oriented validation. Ecology Letters, 25(1), 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13911

3. Nyström, V., Dalén, L., Vartanyan, S., Lidén, K., Ryman, N., & Anders Angerbjörn. (2010). Temporal genetic change in the last remaining population of woolly mammoth. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 277(1692), 2331–2337. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2010.0301

4. Sharko, F. S., Boulygina, E. S., Tsygankova, S. V., Slobodova, N. V., Alekseev, D. A., Krasivskaya, A. A., Rastorguev, S. M., Tikhonov, A. N., & Nedoluzhko, A. V. (2021). Steller’s sea cow genome suggests this species began going extinct before the arrival of Paleolithic humans. Nature Communications, 12(1), 2215. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22567-5

5. Campos, A. A., Cameron David Bullen, Gregr, E. J., McKechnie, I., & Kai. (2022). Steller’s sea cow uncertain history illustrates importance of ecological context when interpreting demographic histories from genomes. Nature Communications 13(1), 3674. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-31381-6